Palimpsest by Gore Vidal

The Vanity Fair Diaries, 1983-1992 by Tina Brown

Happy New Year to you too– my car was stolen in late December and recovered a few days later, sending me on a multi-day odyssey of impound lots, tow trucks, mechanics, and insurance offices, a savage journey into the sun-bleached bureaucratic beast that is LA. There’s only one thing to do when life has kicked you like this and that’s to seek refuge in fluff, in fizz, in piffle– to turn, in short, to the restorative qualities of gossip.

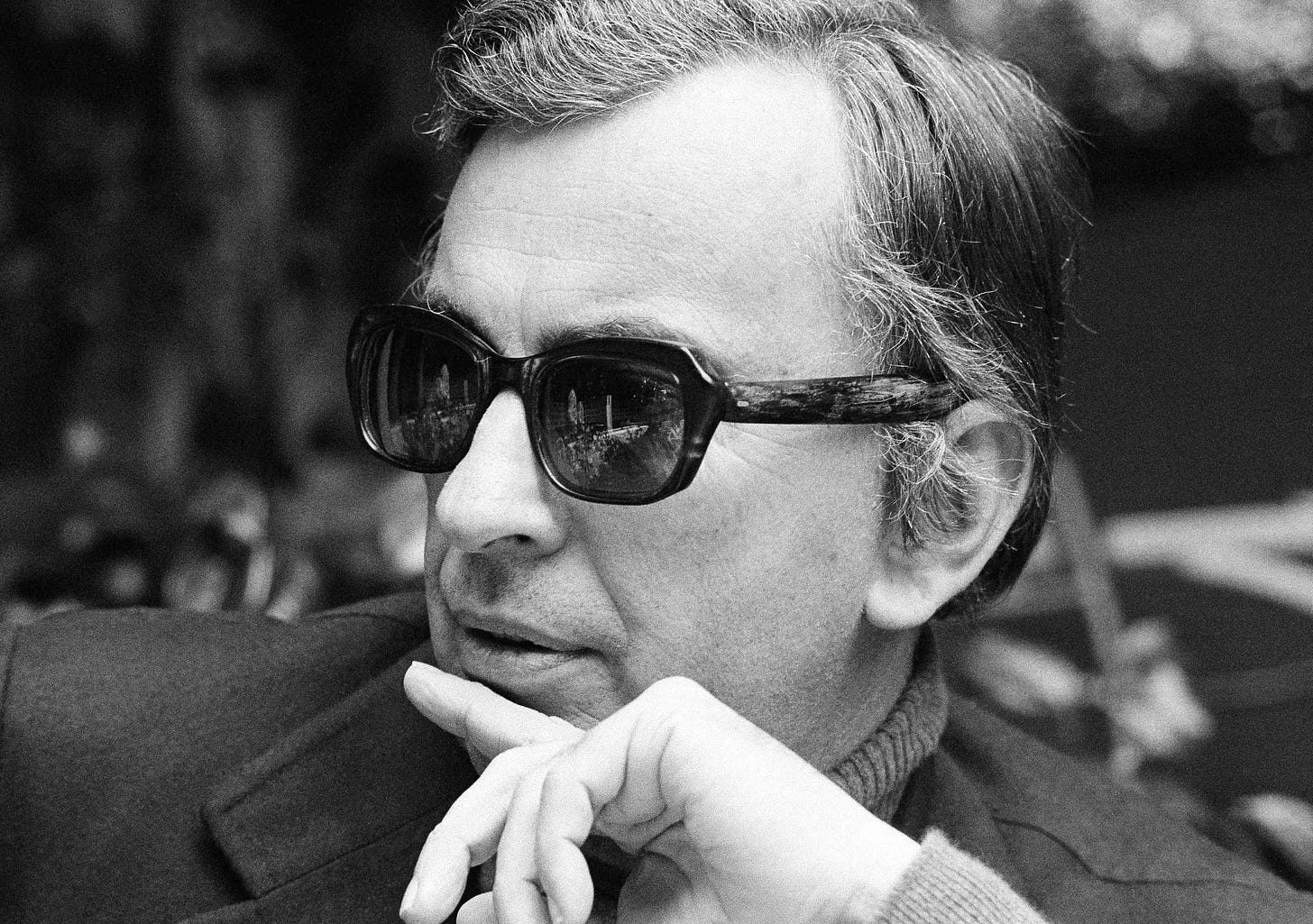

Gore Vidal, that towering man of letters, would probably fix me with an icy stare if he heard me reduce his memoir Palimpsest to the term, but it is fine gossip indeed. Pleasingly non-linear and discursive (as all memoirs should be — I always skip the childhood bits when they put on the cradle-to-grave act), Palimpsest functions as family chronicle, windy musing on the nature of memory, and exploration of Vidal’s foundational tragedy, the death of his improbably-named first love Jimmy Trimble. The book opens with a dizzying, practically Austro-Hungarian chronicle of WASP intermarriage and some medium-interesting tales of his politician grandfather, and ends with some eye-glazing trivialities on the Kennedys, nice if you bought into the Camelot myth, but eminently skippable if you did not1. But the best parts, which form the juicy middle section of the book, are an exercise in score-settling. To hear Vidal tell it, everyone from Anaïs Nin to Allen Ginsberg has slandered and misrepresented him, or as he puts it:

Such is the nature of reputation: The religious man is known to be an atheist; the generous man is called mean. Some years ago an actress told me that everyone knew that Noël Coward liked to eat shit. I was horrified. I knew Coward well. He was as fastidious about sex as everything else. When I saw her recently, she said, “I’ve never forgotten what you told me about Noël Coward, that he liked to eat shit.”

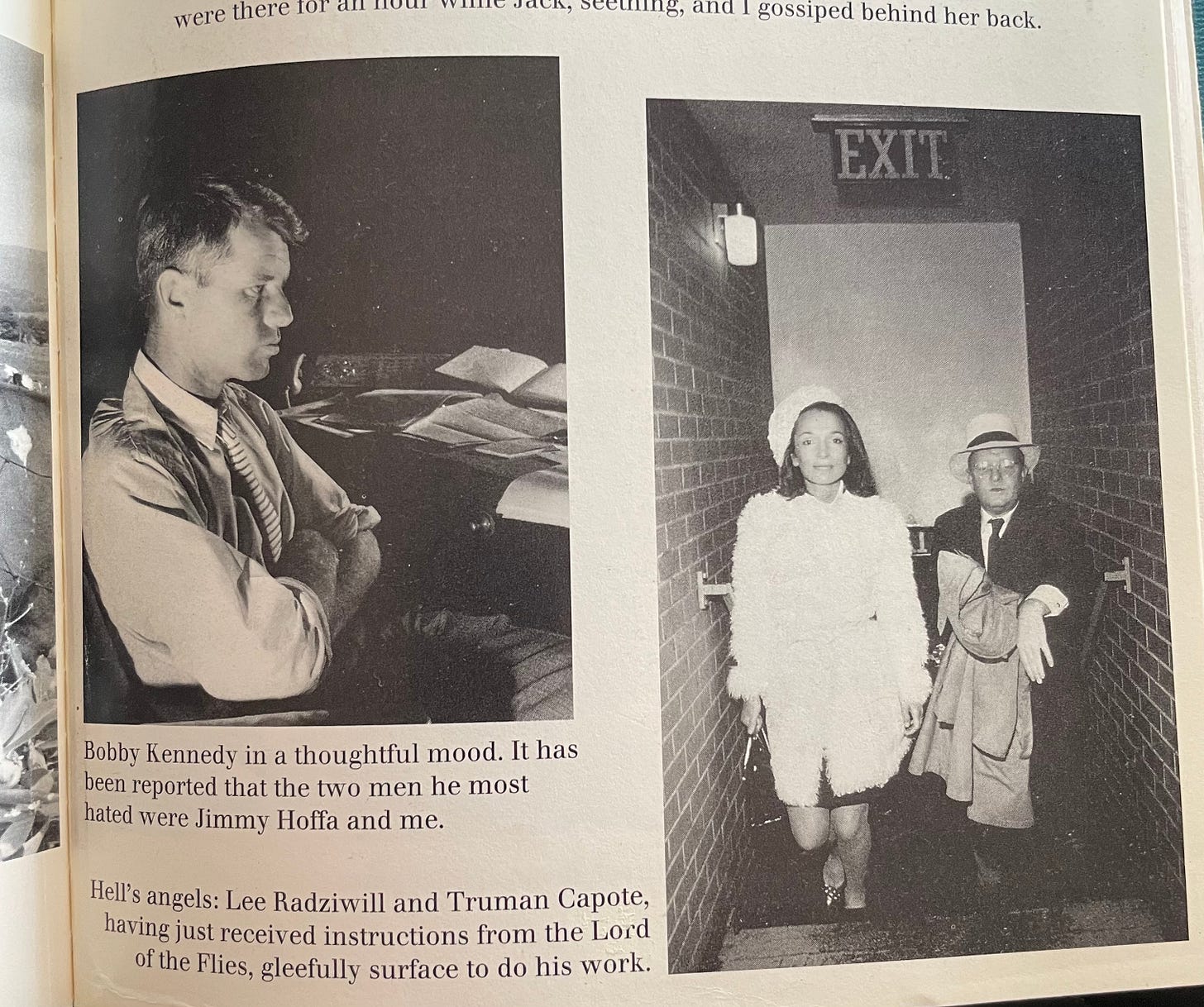

Travel with Vidal and you will meet nearly everyone who matters in 20th century literature and politics. He hobnobs with the Kennedys, fights with Norman Mailer, sleeps with Jack Kerouac, and develops a lifelong enmity towards Truman Capote. The overall tone is that of a decaying aristocrat dictating to an eager-eyed young chronicler. Which, of course, is what it is. For better or for worse, Vidal’s brand of American grandee — erudite and self-assured, crisp and witty – has disappeared from our shores and Palimpsest is a final bit of setting the record straight before Vidal’s brand of aristocrat is replaced with our more vulgar modern rich. Often throughout the book you feel he is trying to make some grander statement: about love, about family, about memory. But these attempts end up feeling somewhat perfunctory. You’re here for the dish.

What are we to make of Vidal, gone now these thirteen years? Will his work endure? He certainly is a capable writer, with a finely tuned style, but one can’t help but feel, reading Palimpsest, that he was catapulted to pre-eminence because of his status as a provocateur in his social set of wealthy WASPs. He could be trusted to say outrageous things precisely because he was to the manor born. You can feel something of the naughty child in him; he’ll venture far outwards to the edge of acceptable opinion for his social set, and make many real enemies but never say anything that would get him permanently disinvited from the Kennedy compound. At its best it is a bracing forthrightness and candor but at its worst it is a kind of court jesterism.

We see this in his politics; a curious amalgamation that seems to anticipate certain modern strands of what is sometimes called the post-left. He makes much of his idea that same-sex attraction is common and normal, but disdains “queens” and “fairies,” and he is fiercely anti-imperialist and anti-interventionist, but in a very pre-WWI America-first way. Though I imagine he would have been a Bernie supporter, he reads as more of a Compact than a Jacobin type today2. As for his literary essays, they’re droll and incisive and generally worth reading, but as a critic he lacks that certain spark you find in a Wilson or a Trilling, the former’s magnificent, thundering sentences and the latter’s cool, analytical eye. I haven’t yet read any of his novels, but it seems as if their audiences are in peculiar silos that don’t cross over — earnest LGBT history types like The City and the Pillar as a compliment to Giovanni’s Room or A Single Man, the Paglia/Red Scare set praises Myra Breckinridge, and Julian, Burr, and Lincoln seem to still maintain a robust following of normie history dads. As a career it’s certainly nothing to be ashamed of but one gets the feeling that he is a bit of a B+ student in every field, dependable and entertaining but somehow coming up slightly short. Nevertheless, it’s valuable to have these 20th century Zeligs around, who touched politics, media, and literature and made their life a catalogue of their times, and you couldn’t choose many more interesting narrators to take you through the century than the imperious Mr. Vidal.

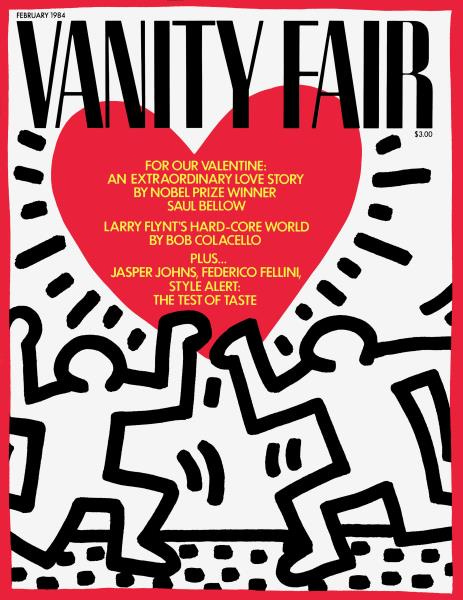

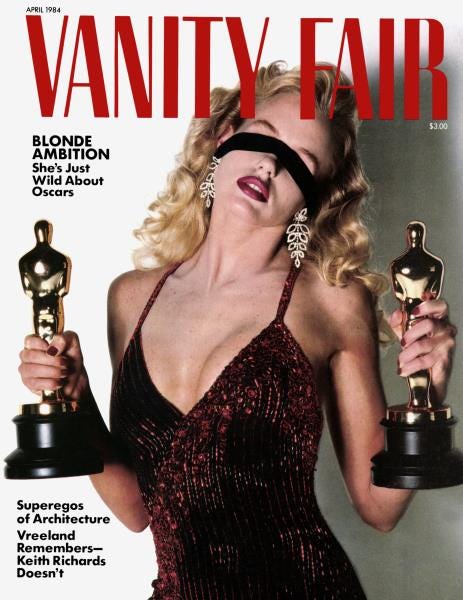

While attempting to print out some insurance paperwork at my local library I spied a post from the Mars Review of Books’s Noah Kumin mentioning The Vanity Fair Diaries, Tina Brown’s record of her time as a media power player at the height of eighties glitz and excess. It sounded like the ideal refuge from my frazzled state and as luck would have it, there was a copy on a shelf not twenty feet away. I’ve always paid careful attention to these sort of synchronicities when it comes to my reading material and though this habit has left embarrassing gaps in my education, it has also yielded delightful surprises, of which The Vanity Fair Diaries now stands in the first rank. I blew through it in two lazy, indulgent post-Christmas days.

For someone who got interested in journalism well after the Internet and ’08 crisis, the book is like a dispatch from an alien world. So much goddamn money! Instead of the ambient desperation and tightfistedness felt even among the good magazines these days, the high-level Condé Nast figures in these pages are at the center of New York high society: paying top dollar for stories, throwing extravagant parties, and lunching at the Four Seasons every day.

Into this circle of Trumps, Reagans, Astors, and Kissingers3 steps Brown, a fresh-faced import who made her name skewering the cream of British society in Tatler magazine. Her outsider perspective on the furious pace of Manhattan media life makes for some perceptive observations on British mordancy and American exuberance:

The work ethic and energy here are so different from England. It holds you up with invisible hands and makes you feel buoyant when you get out of bed. I notice this difference especially when I call London to talk to writers and I hear the rain in their voices — “Hull-o,” with a downward intonation.

Despite her self-portrayal as an provincial Brit transfixed by American flash and whizz, Brown is an operator and if you read The Vanity Fair Diaries even a little esoterically, what emerges is something like I, Claudius in high heels. When Brown is scouted for Vanity Fair, the magazine has recently relaunched and is struggling to recapture its jazz age mystique. She quickly power plays her way into ousting yesterday’s man, the longtime Condé editor Leo Lerman4 and quickly builds the magazine into the flashy, chic voice of its era, while staying on the good side of a host of New York society queens, Hollywood sharks, and the nebbishy, mercurial Condé Nast owner Si Newhouse. But though she might be a bit more ruthless than she portrays herself as being, her passion and drive seem entirely real, and she fiercely defends and advocates for her staff and her stories. While I assume some judicious editing has been done to prepare these for publication, the person that emerges out of the pages is quite charming, sharp and savvy, with a real pride in creating a magazine that is both glamorous and intelligent. As she puts it:

It’s more the VF attitude to fame and the mix of stories that ensnare the reader with juxtaposition. We give intellectuals movie star treatment and movie stars an intellectual sheen and the same is true of the audience. Brainy people in our pages seem more glamorous and movie people seem more substantive.

This is exactly right. I had always wondered if it was just the rosy glow of the past that made its intellectuals seem so appealing (think of all those video clips of Sontag and Paglia that go viral every few months), but I think there’s more to it than that. It’s not exactly having intellectuals side-by-side with celebrities, though that doesn’t hurt. It’s creating a world in which the kind of work that intellectuals do, as well as conflict reporters, longform journalists, and short story writers, is assumed quite naturally to be not just as important but as pleasurable as a glittering photo shoot or a juicy celebrity story, even if it’s a different kind of pleasure. At its best, Brown’s Vanity Fair operates with this assumption. Even the party planning, frivolous as it seems, serves to legitimize the magazine’s centrality to culture and thus the centrality of its writers and its work.

After nine years of helming the Vanity Fair turnaround, the diaries end with Brown leaving to take over The New Yorker. Despite fears she would revamp it in the same glossy style, she recognized that sense of intellectual glamour and, though she did some modernizing and added photography, the magazine largely retained its egghead reputation (though not everyone thought so). I hope we get a New Yorker Diaries one day.

Needless to say, the pure pleasure of reading these vivacious diaries is marred somewhat by the fact that magazines today are not nearly so important, so rich, so interesting, or so self-assured. It is sad to feel as if you missed a golden age. But the advantage of reading books like this (as well as Peter Hall’s diaries, which I wrote about a few weeks ago) is that reading about the lives of these impossibly energetic, self-motivated, ambitious people prompts you to take stock of the sparks of life around you and makes you want to nurture them, to join forces and create something as exciting, fresh, and pleasure-inducing as Vanity Fair was in its time. It’s not like this is institutional cultural power, but when I threw my Sir Gawain reading last week, and the post-reading merriment was in full swing, we might have been drinking High Life in a small gallery in a nondescript Chinatown building instead of champagne in the Plaza ballroom but I nevertheless felt a little like Brown: exhilarated at the possibility of the social world, of being among intelligence and talent. Media might boom and bust, but that survives.

Hope everyone had a relaxing holiday season and pray that my ravaged 2018 Kia Soul returns from the mechanic safe and sound soon.

There is also some funny-in-retrospect Clinton boosting, both Bill and Hillary. Vidal claims that they genuinely wanted to improve society and were savaged for it. One wonders what Gore would have to say about this shining pair today. Then again, maybe he would have been on the flight logs.

Consider also his essay “Pink Triangle and Yellow Star,” a gleefully icy riposte to a forgotten piece of genteel homophobia by the neoconservative intellectual Midge Decter. It has to be said that while the neocons were quick to throw around bad faith accusations of antisemitism, they might have had a bit of a point when they took issue with statements like “No matter how crowded and noisy a room, one can always detect the new-class person’s nasal whine.” Overall the essay is attempting to make common cause between the Jews and the gays, and there certainly doesn’t seem to be any kind of virulent race-level prejudice in Vidal, but one can see here how his purported radicalism doesn’t prevent him from quietly shutting the doors of the country club to interlopers.

Later in the essay: “She tells us how, in the old days, she did her very best to come to terms with her own normal dislike for these half-men—and half-women, too: ‘There were also homosexual women at the Pines, but they were, or seemed to be, far fewer in number. Nor, except for a marked tendency to hang out in the company of large and ferocious dogs, were they instantly recognizable as the men were.’ Well, if I were a dyke and a pair of Podhoretzes came waddling toward me on the beach, copies of Leviticus and Freud in hand, I’d get in touch with the nearest Alsatian dealer pronto.” Guilty LOL.

Seriously, Kissinger shows up in these pages an awful lot— I had no idea Henry was such a party girl.

Whose diaries I have just ordered and hope to read alongside Graydon Carter’s forthcoming memoir for a later post.

Fantastic piece. Give Vidal’s novels a shot. Myra, Burr, Washington D.C.. All great!

Really enjoyed this! My favourite Vidal piece is his essay on the American postmodernists (“American Plastic” I think it was called?) wherein he accuses them of being always jocose but never funny. It’s very cutting, tho of course part of the pleasure of reading it today is that he was — at least with Pynchon and R. Barthes, and whether he knew it or not — boxing above his literary weight class. That’s my ideal paradigm for criticism: the Achievement-Gap Relationship.