I always had high expectations from theatre, on account of the fact that I was lucky enough to have a high school drama teacher who took the form extremely seriously. No productions of Grease or Oklahoma for us; in my tender adolescence I was reading and performing Beckett, Ibsen, and Brecht, and going on field trips to his tiny black box company to see Jungian interpretations of The Tempest. I was never a very good actor, but what did it matter? I wore the mantle of “theatre kid” proudly, as the mark of a serious, striving intellectual pursuit, a lacerating adventure into the reaches of the self. Then I went away to college and discovered that for most people, this was not, to put it lightly, the case.

It has always been a bit of a disappointment for me. My friend and I joke that you have to go see several plays per year “to see if they’re still bad.” I have had great nights at the theatre in my life and seen brilliant performances, but it can’t be denied that the art form is not in particularly rude health. Broadway — dead, dead, dead. Off-Broadway and regional largely sanctimonious and overwritten, “political” self-flattering or perhaps “transgressive” in a 1970s sort of way. You wonder what it would feel like to live at a time when the world’s oldest narrative art form was treated not as a dutiful obligation or a lark or the minor leagues for a job on Succession but as a vital part of the living art of the country.

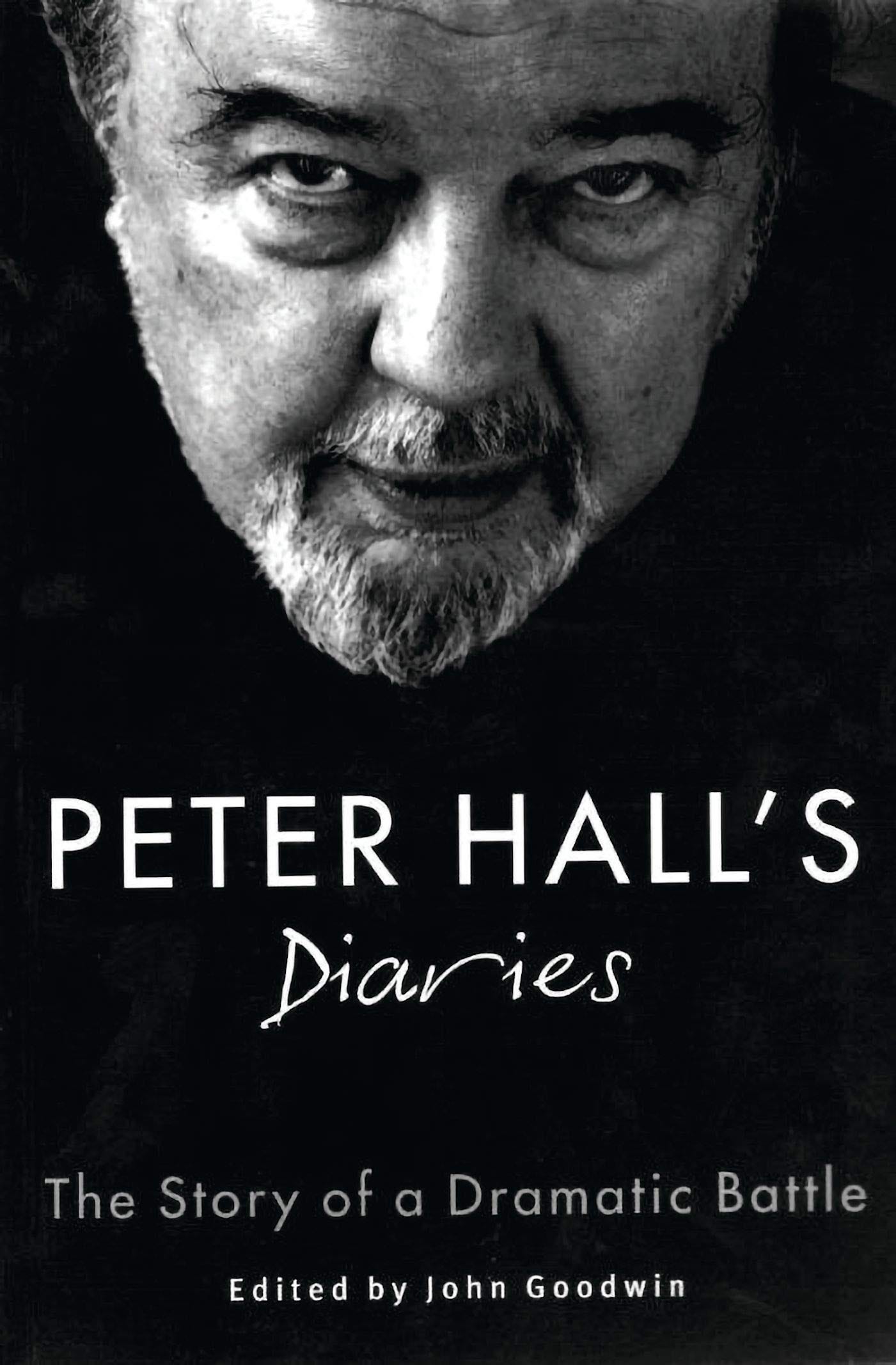

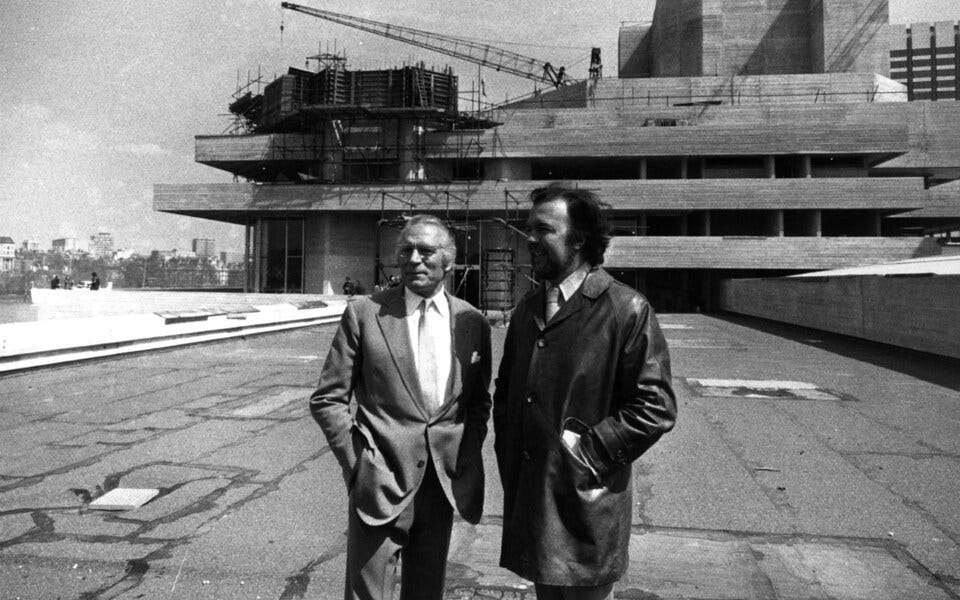

Which brings me to Peter Hall’s diaries of his time running the National Theatre from 1972-1980, a great book which functions simultaneously as a compendium of wise and witty observations about theatre and directing, a memoir of leading a contentious and dysfunctional organization, and an Amisian comic novel with a hapless, self-defeating protagonist. Hall was one of the most important theatrical figures of the twentieth century, founding the Royal Shakespeare Company when he was only 29 and setting the template for the absolute attention to rhythm and verse that defined Shakespeare in the 20th century. As we join him, Hall is preparing to take over the National Theatre from Lawrence Olivier and move them into a glittering new brutalist theater.

The early years are defined by Hall’s attempts to break free of Olivier, who is rendered as a comic King Lear; he insists he is ready to give up power but when the time comes he dithers. Thus much of Hall’s time has to be spent flattering and cajoling the elder statesman in passages like the below:

Messages that Larry urgently wanted to see me. I know from past experience that the only thing to do in these circumstances is to see him quickly. I had to invite him over to the flat because I was collecting the children from school. I was uneasy about this as I always vowed I would never let him see the flat. He makes many remarks about it being higher off the ground than his… I poured vast quantities of whiskey down him and he became quite expansive. He is in good form.

Hall eventually gets command of the ship and has to supervise the National’s move to the South Bank, which is excoriated in the press for being far over budget and deadline. All this in a country where social democracy has all but run out of runway and there is little appetite for state-subsidized art.

(As I was reading the diaries I listened to The Rest is History’s “Britain in 1974” series. I had vague images of Thatcher, striking workers, the IRA, and energy cuts but God, I had no idea how bad it got over there — the country was genuinely on the verge of collapsing for nearly a decade.)

It’s incredible the power that the success or failure of the National Theatre has in shaping the psyche of the country. Hall’s taxi drivers and doormen mention they’ve been reading about him in the papers. Splashy reports on its tribulations fill the front pages, and he begins to fear recognition in public spaces. Labor troubles run through the foreground as well as the background. A significant subplot of the book is Hall’s contentious relationship with the stage employees’ union, who (according to his telling) behave unreasonably; often making impossible demands for compensation and then striking when the National cannot or will not fulfill them. It all dovetails with Hall’s working through the fact that he is no longer a young talent on the make but part of the Establishment he rose against. The labor troubles make the inherent tension of making commercial art disquietingly real, as various left-wing playwrights and directors eventually turn against the union and Hall votes Conservative for the first time in his life.

Perhaps a few of the NT’s stumbles can be fairly blamed on Hall’s Falstaffian appetite for new experiences. He directs three major plays a year, oversees the bureaucratic workings of the NT, and spends the rest of his time directing commercials and films, going on talk shows, being flown out to various countries on the Concorde, and having long, boozy lunches with artists and politicians (Prime Minister Harold Wilson pops up regularly as a dinner companion, even as the country is going through extreme crisis). On his rare days off he reads two volume treatises on Jacobean theatre from cover-to-cover. The appetite is insatiable, the mood manic-depressive. He barely seems to sleep. He is wracked by money troubles personal and professional, plays are always on the verge of collapsing, bad reviews send him into a funk for days. It’s comic, but at the end of the day his ferocious determination and drive makes him into a heroic figure1. It made me want to work, to create, to produce (and have more long, boozy lunches) — otherwise, what are my days for?

All the while he is producing something vital. Around Hall are some of the greatest theatrical talents who ever lived. There are old lions like Olivier, John Gielgud, and Ralph Richardson (Harold Bloom said after seeing Richardson as Falstaff, no one else could measure up). There is a new generation of actors who would become household names (Ben Kingsley, Patrick Stewart, Ian McKellen) and actors who deserved to (the extraordinary Alan Howard, whose great declarative force is what I imagine must have defined the great actors of Shakespeare’s day). The plays are a mix of classics and new work from names like Pinter, Beckett, and Stoppard. And while Hall frets about budgets and tortures himself over artistic integrity, to have the resources at his disposal that he does to perform not-exactly-crowdpleasers like No Man’s Land, Volpone, and Tamburlaine the Great seems unimaginable.

Unlike most diaries which are by nature shapeless, there is a magnificent climax in the last section as Hall deals with a catastrophic labor dispute at the same time as he attempts to direct a masked Oresteia and the newly written Amadeus. His eventual triumph with the latter is very satisfying; at the cost of (it is hinted at) his personal life and his last expense of energy, he has finally created a commercial hit without sacrificing artistic vitality and set the theatre on a steady course for the future. I found it genuinely very moving.

I suppose the real appeal of theatre is the quest for perfection. It’s like Wagner’s operas. No matter how sublime the music is, there will always be something faintly ridiculous about zaftig men and women in viking helmets (or “CEO of Odin Corporation” modern dress) acting out the birth and death of the infinite cosmos and the terrible power of the gods. Yet unconsciously we all know that there is some sort of platonic perfect form of a performance, where the power of the stage is so overwhelming that for the entire run time one forgets the uncomfortable seat and the silly props and instead sees the real gods and monsters, is plunged into the abyss of creation itself. Somewhere out there is a perfect Hamlet, a perfect Oedipus, and for hundreds and thousands of years (respectively) the task of each new interpreter has been to try to find it. We never will, of course. But we can beat a few small strokes against the current when the attention of several brilliant artists is brought to bear on the problem and given freedom and funding. And in the middle of the 20th century, such a thing happened in Britain.

The diaries caused a furor when they came out and towards the end of his life the actor Michael Blakemore wrote a book called Stage Blood which paints Hall as smug, vain, and ruthless. I haven’t read it and it could easily be true, my account of Hall is that of a literary creation and I don’t pretend to know what he was really like.

Great piece. I strongly recommend the Blakemore book - there's absolutely no love lost between him and Hall, and he's a fascinating figure. Not as bombastic and self-sabotaging as Hall, of course ...

The Amis reference has me intrigued, though I'm curious whether you're referring to Kingsley or Martin? Sounds like the former, but I haven't read so much of the latter as to know...