September 9

I hate flying so I’m on the train. The Amtrak is slow, jerky, and always late, but you do ride straight along the edenic coast of California. I share a table in the observation car with an older man poking at his laptop. I’m reading War Music, which has a way of attracting attention. I describe it to him and he tells me about living in the South of France and says I should read A Sentimental Education while I’m still young. God Bless America! God Bless The Rails!

September 11

Green Apple Books in the Richmond district of San Francisco is the greatest bookstore in the world, and i’ll stand on any other store’s display table and shout it. Forget the global totebag merchants, your Strands, your Foyles’. They might have what you’re looking for, but so what? They have everything. They’re all things to all people and nothing at all. Green Apple might have 15 books in a shelf on say, birdwatching, but all 20 will be fascinating, half of them you will have heard of and been meaning to get to, half of them you’ll never have heard of but immediately add to the ever-growing list in your head. And because the bulk of their business comes from the requisite stacks of NYT bestsellers in the lower section and because people with niche interests are a vanishing breed in the city, the stocks are constantly replenished but the good stuff in the used upstairs section sticks around. I’ve been meaning to buy George Steiner’s No Passion Spent there for five years now and every time I go, three or four times a year, there it lies patiently awaiting me (I didn’t buy it this time, either). If I was in charge of sainthood the place would be immediately consecrated and the book buyers there would be canonized and made the subject of odes, statues, and devotional amulets.

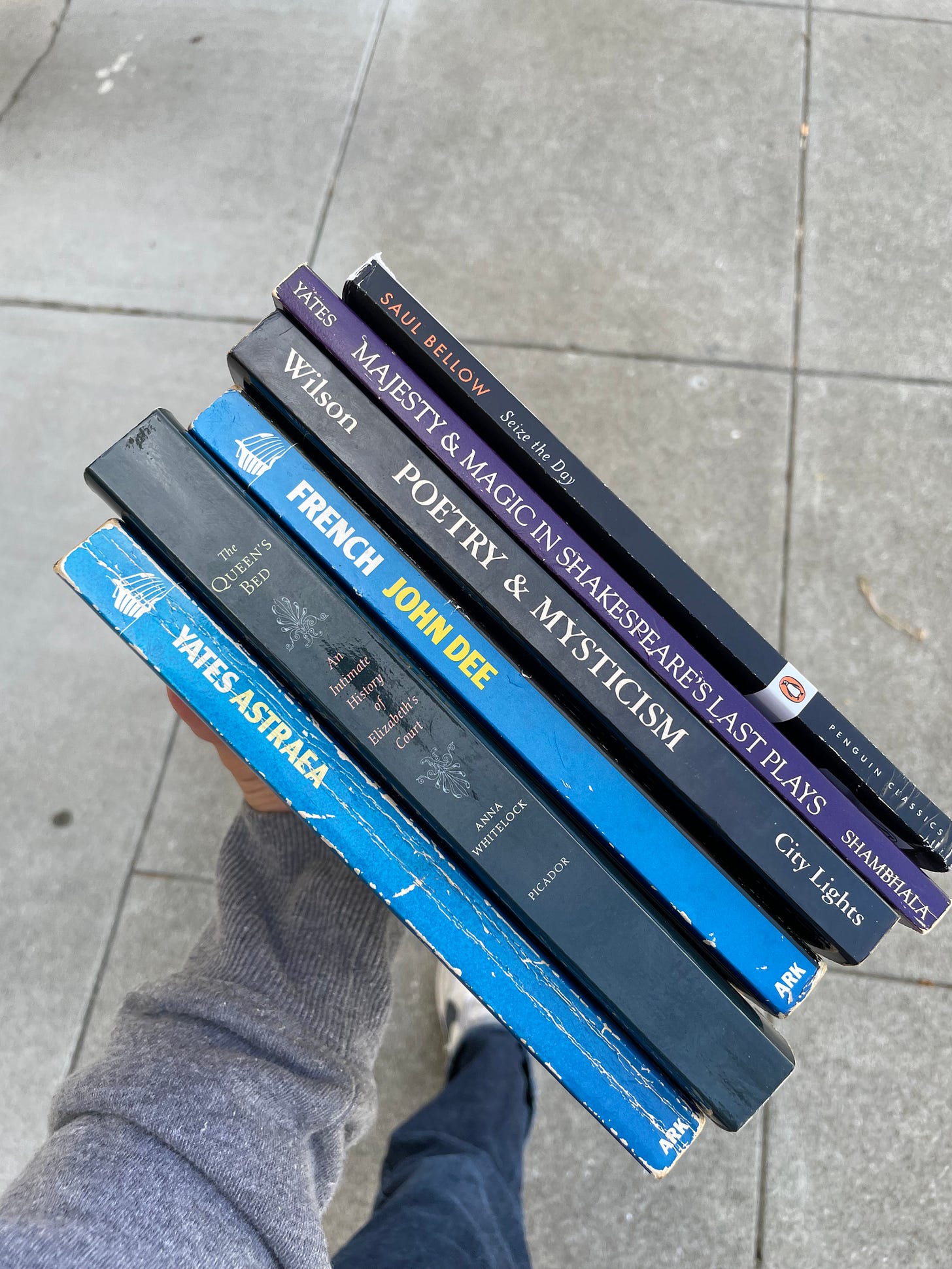

Anyway I walk in and I immediately spot in the Shakespeare section Frances Yates’ Majesty and Magic in Shakespeare’s Last Plays, which I’ve never even heard of despite being a certified Yates head, priced at a reasonable we-know-what-we-have-but-we’re-still-cutting-you-a-deal rate of $30, a bit more than I wanted to spend but you don’t see late Yates every day (her books were republished by hippy-dippy publisher Shambhala, which could account for their presence in the Bay Area). Then - shock and horror - I go through the English history section and they have more Yates: Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century as well as - Oh No! - Peter French’s biography of John Dee and Anna Whitelock’s The Queen’s Bed, which I had saved to my Amazon wishlist literally earlier that day. I’ve been trying to write something set in the Elizabethan era for months now (and putting off reading The Faerie Queene, which I know I will have to do), so I write it all off as research. Then, browsing in the poetry section, I’m flipping through Colin Wilson’s Poetry and Mysticism when a Grateful Dead ticket from 1994 falls out. September 17, 1994 at Shoreline Amphitheater; nearly twenty years to the day. Jack Straw opener, last recorded It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue as an encore. Since Deadheaddom is another of my morbid afflictions, and I always listen to signs and portents, into the basket it goes. I also pick up The Blithedale Romance and Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day.

September 11

I return the next day and head to the medieval history section. I’ve been wanting to truly understand the period for a long time but this recent compulsion was occasioned by a recent visit to Medieval Times, America’s finest jousting-based dinner theatre experience. I expected to enjoy myself in a campy sort of way and found myself completely taken in, spurred on by the very reasonably priced beers they sell in giant collectable steins, screaming for the victory of my Red and Yellow knight. A handsome man but a bounder and a rogue, he was immediately knocked off his horse and resorted to the most unchivalrous attacks to the groin and from behind. When he was dispatched I shifted my allegiance to the Green Knight, thinking of Gawain and the barrow-mounds, the wild wordless earth. He won! There was also falconry. An incomparable experience, even if the decor did misspell “chivalry”.

So the middle ages have been on my mind, that brighter, stranger world. I need to read some primary sources, I decide, so I pick up Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich as well as The Civilization of the Middle Ages by Norman Cantor and The Pursuit of the Millennium by Norman Cohn. The latter has a long section on the Peasants’ Revolt, which I know next to nothing about except for the names Wat Tyler and John Ball and the phrase “when Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?” It’s incredible how a few evocative names and phrases can roll around in your head and create such an itch to know more. I also buy John Donne’s Selected Prose so I can read Biothanatos, his treatise on suicide and a lavishly illustrated volume called The Pagan Dream of the Renaissance.

They have a ton of old Penguin Iris Murdochs (the old pocket-sized ones, only slightly bigger than a cell phone - bring those back!), and I’ve been meaning to read her, so I buy The Black Prince. To my surprise and delight, the checkout clerk is also reading Murdoch— Existentialists and Mystics. I didn’t think there were any such people left in San Francisco. He recommends The Sea, The Sea.

September 14

I took the train again, up to Seattle - a somewhat arduous overnight journey. Fun once, but not good to do regularly. If you don’t have the luxury of your own seat row you’re forced to sleep in a chair next to a stranger and the conductors are vigilant about making sure you don’t light out for the rows that are only temporarily empty. As we speed through the night I start listening to one of Geoffrey Hill’s Oxford lectures, not quite knowing what to expect. I’ve never even read the guy. But from genuinely the first second I am hooked. The VOICE! My god, it’s like listening to an ancient oak tree. I resolve to read anything of his I can find.

Bleary in the morning light in the observation car I talked to another stranger, a portly jolly Tolkien fan type fellow that you encounter often in the Pacific Northwest, about the book I was reading, The Once and Future King, the one he was reading, Memoirs of an Amorous Woman from 17th century Japan, and our shared feelings for The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon. Whenever my friends mention Amtrak encounters they’re with people just out of jail who share their murderous or perverted fantasies to their unwilling seatmates, but mine have been nothing but charming.

September 16

By the leafy confines of the University of Washington lies Magus Books, which is not as perfect as Green Apple but comes quite close, with a fascinatingly comprehensive collection of occult books behind the counter (donated, says the legend, by a dying software millionaire). I have a fair amount of store credit there from when I lived in the area so I burn through it all. My first pickup is Martin Amis’s The Information, because I saw a Goodreads review of the book consisting of nothing but the following passage:

Richard sat in Coach. His seat was non-aisle, non-window and above all non-smoking. It was also non-wide and non-comfortable. Hundreds of yards and hundreds of passengers away, Gywn Barry, practically horizontal on his crimson barge, shod in prestige stockings and celebrity slippers, assenting with a smile to the coaxing refills of Alpine creekwater and sanguinary burgundy with which his various hostesses strove to enhance his caviar tartlet, his smoked-salmon pinwheel and asparagus barquette, his prime fillet tournedos served on a timbale of tomato and a tapenade of Castillian olives--Gywn was in First.

I also find the Geoffrey Hill I was looking for and another Bellow, Mr. Sammler’s Planet (I read Ravelstein and Herzog earlier this year and knew I had no choice but to make my way through the lot). Because I am nothing if not romantic, I also buy my girlfriend Slavery and Social Death by Orlando Patterson.

Later, I’m in a coffee shop, still reading War Music, when another older, ponytailed gentleman comes up to me. “Do you like the classics?” he asks. When I respond in the affirmative he launches into a fantastically detailed summary of a science fiction novel in which women live in walled cities and men are reduced to feral hunter-gatherer status. Fifteen minutes later I surmise that the novel has something to do with The Trojan Women. He ambles away.

September 20

Lord, make me responsible in my purchases — but not yet! Back home in Los Angeles I’m out for a run listening to a podcast discuss two essays by, again, Martin Amis. I had barely given a thought to him a month ago but now he keeps appearing in my peripheral vision. They discuss an essay on Bellow, which seems to overstate the case a bit, and then read from an essay on the unknown-to-me V.S. Pritchett, which begins thus:

V.S. Pritchett's short stories are retrospective, provincial, formless and feminine. His is an art that does not care how peripheral it sometimes seems. There are no twists, payoffs, reverses, jackpots or epiphanies. Pritchett never rubs life up the wrong way, and is happy to leave only. a faint shine on its fur. He uses the forms and addresses of minor art, yet there is no one quite like him - no one alive or male, anyway.

It continues on:

Sentences that resemble train-wrecks - 'The cook took a look at the book' etc. - are common enough in genre fiction, where simple inattention or mercenary haste must claim responsibility. And when, for instance, Anthony Powell writes a phrase like 'standing on the landing' you feel that it is the result of mandarin unconcern or high-handedness. Pritchett's prose is full of these jangles - 'Sitting behind the screen of the machine' is a random example - but the effect is entirely appropriate to his way of looking at life. Life does rhyme: it rhymes all the time. Life can often be pure doggerel.

Pritchett's responsiveness to the quotidian is one of the reasons his stories seem formless; they are not comic, tragic, romantic, farcical, or like anything else that has a shape. Pritchett is locked into the kinks and rhythms of what he elsewhere calls the 'native ennui'.

I’m simply helpless before stuff like that. Grimacing, I buy the book off Amazon, swearing that this will be my last indulgence. And it is, for a little while.1

And it was a good indulgence, because reading the Amis, which I’m not yet done with, helped me get back into writing here regularly. He is so bold, he just says stuff with such assurance. I get tied up in knots making sure I have evidence for every claim and can back up all my statements and I never get anything written at all. Reading some of the really good aphoristic critics, like Amis and my beloved Schjeldahl, helped me realize you can be a bit outrageous, go on instinct, you can throw ideas out there to see if they sink or float. In short — people care that you’re interesting, not right.

"Pritchett never rubs life up the wrong way, and is happy to leave only a faint shine on its fur." All right that's good.

You're getting in pretty deep with all this Renaissance stuff, it seems to me.