Gossip III: Harpo at the Algonquin & The Last Days of Groucho Marx

"Harpo Speaks!," "Groucho and Me," and "Raised Eyebrows"

Harpo Speaks! by Harpo Marx with Rowland Barber

Groucho and Me by Groucho Marx

Raised Eyebrows: My Years Inside Groucho’s House by Steve Stoliar

In Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day, a novel so dense and complicated that even the hardiest minds of Wikipedia seem to have given up trying to summarize the plot, a character named Frank Traverse, adrift in Cripple Creek, Colorado around the turn of the century, meets a teenager named Julius. Julius is a traveling vaudeville performer whose partners have run out on him with the box-office take. Hoping to make enough money to get back to “dear old East Ninety-third,” he has taken a job delivering groceries via covered wagon, despite having never seen a horse outside of the Coney Island merry-go-round. This minor interaction, easily forgotten among this novel’s 1100 pages, is of course a cameo from the young Julius Henry “Groucho” Marx, and the incident is lifted directly from his autobiography Groucho and Me.

Stanley Cavell, the American philosopher whose books bear such ghastly titles as The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy and Cities of Words: Pedagogical Letters on a Register of the Moral Life had this to say when he wrote about the Marx Brothers for the London Review of Books:

I have been aggrieved to hear Groucho called a cynic. He is merely without illusion, and it is an exact retribution for our time of illusory knowingness that we mistake his clarity for cynicism and sophisticated unfeelingness.

Harold Bloom’s “short list for the American Sublime” included the following: As I Lay Dying, Wallace Stevens’ “The Auroras of Autumn,” Hart Crane’s “The Bridge,” and compositions by Bud Powell and Charlie Parker. From the hundred-year history of American cinema he included only one scene: the carnivalesque war scene that forms the climax of Duck Soup.

But now I’ve dropped too many names—what am I, Margaret Dumont? I mention these intellectual heavyweights not just to flex my own erudition or to over-legitimize a seemingly low form but rather to proffer that there really is something elemental and pure about Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and (I suppose) Zeppo. Something of divine anarchy, something of the holy fool. In their twenty years of Marx Brothers movies, from the rough-draft The Cocoanuts through the Animal Crackers-Duck Soup golden era to their dull and weary final films A Night in Casablanca and Love Happy there are many moments of drag, bloat, schmaltz, and harp solos. There are jokes that don’t work and jokes whose meaning have been lost to time. But as a package, it is such an unadulterated blast of happiness that it perks me up simply to think about it.

It’s hard to explain it. I recently rewatched City Lights (at the Netflix-owned and operated Egyptian Theater in Hollywood; the effect was somewhat similar to a conqueror’s palace in which the quaint religious relics of the subjugated population are displayed) and while Chaplin is undeniably a great artist, the guy is just so goddamn saccharine. With the Marx Brothers, you never get the feeling that they wish they were playing Hamlet. They feel more like deities, like expressions of single aspects of humanity rather than complete people—Groucho, pure wit, Harpo, pure id, Chico, pure self-interest1. They possess a Bacchic, manic edge. Even in the most sedate moments of their films, complete pandemonium and anarchy are lurking in the background, waiting to be unleashed. And when Groucho launches into a monologue of free-associative near-hysteria, or when Harpo steps into a scene with his beautiful one-brain-cell expression, I feel I am witnessing something perfect, like a sonnet. If I had to distill their importance to me into one lesson it would be this: there is great philosophical and spiritual value in being extremely, uncomplicatedly, perfectly silly.

I became interested in the Marx Brothers when my father showed me Animal Crackers at an early age, but I became interested in the books by and around the Marx Brothers when I picked Harpo Speaks! off the shelf in the massive Film & Entertainment Biography section of North Hollywood’s Iliad Books, a place filled so comprehensively with the testaments of forgotten entertainers that it serves as a monument to the ravages of time, like “Ozymandias.” I’m glad I rescued it, because Harpo Speaks! is one of the great show-business autobiographies and Harpo, the famously silent clown, is a wry, gentle, happy-go-lucky, and immensely likable storyteller. There is hardly a word about making Horse Feathers or A Night at the Opera in the book, but many incredible scenes of young Harpo growing up with his brothers in turn-of-the-century New York, playing the piano in a Long Island brothel, touring the country as a penniless, struggling vaudeville act, and finally making it in high society as what he calls a “full-time listener” at the Algonquin Round Table and in the country clubs of Beverly Hills. It’s a lot like World of Our Fathers, Irving Howe’s exhaustive history of the Yiddish-speaking immigrant experience, but with better jokes.

Here’s a section from the early part of the book, describing Election Day on the Upper East Side in the early 1900s:

The great holiday lasted a full thirty hours. On election eve, the Tammany forces marched up and down the avenues by torchlight, with bugles blaring and drums booming. There was free beer for the men, and free firecrackers and punk for the kids, and nobody slept that night.

When the Day itself dawned, the city closed up shop and had itself a big social time—visiting with itself, renewing old acquaintances, kicking up old arguments—and voted.

About noon a hansom cab, courtesy of Tammany Hall, would pull up in front of our house. Frenchie [Harpo’s father] and Grandpa, dressed in their best suits (which they otherwise wore only to weddings, bar mitzvahs or funerals), would get in the cab and go clip-clop, in tip-top style, off to the polls. When the carriage brought them back they sat in the hansom as long as they could without the driver getting sore, savoring every moment of their glory while they puffed on their free Tammany cigars.

(If we’re going to have political corruption, I’ll happily take the “free beer and carriage rides” variety over what we have now.)

The Marxes were famously managed by their tireless and domineering stage mother, Minnie Marx, who marched them around the one-horse towns of the country, refining their act, until they worked their way up to vaudeville royalty, then Broadway, then Hollywood. Harpo’s evocations of the world of vaudeville, which make up a sort of long travelogue in the middle of the book, a series of disconnected memories conjured up at will, are like reading a testament from a lost world or a record of a vanished civilization. Though to be fair, one that consisted of acts like this:

In Laredo we shared the bill with one of the saddest vaudeville acts I ever saw-"The Musical Cow Milkers." It was a team. The guy led a live cow onstage and while his wife, in sunbonnet and pinafore, squatted on a stool and milked the cow, they sang duets.

Because Harpo had a rise without a fall, and seems to have mostly enjoyed his celebrity, met the love of his life, and died a sweet, well-adjusted family man, the second half of the biography is inevitably a bit less interesting, though just hanging out with Harpo is pretty good too, and there’s a great section on Harpo’s adventure as the first American comedian to tour Soviet Russia. If you’re the sort of person who gets a kick out of anecdotes about dusty figures like Harold Ross and Noel Coward, which I unfortunately happen to be, there’s still much to enjoy. What struck me most about Harpo Speaks!, though, was realizing that the utterly foreign world it describes in its first half was only two lifetimes away—Harpo’s son, Bill Marx, is still as sharp as his father at the age of 88 and you can still find him appearing on kitschy YouTube channels and guesting on podcasts. Harpo saw the vaudeville world completely disappear, replaced by film, which must have seemed to many as cheap, soulless, and vulgar as artificial intelligence does today. Now film has largely lost its mandate as America’s collective unconsciousness and though it will likely to remain with us in some form, is on the precipice of becoming something new and strange. Two lifetimes is not very long and I have to say, I didn’t expect a Marx Brothers autobiography to get me thinking so much about how the passing of the ages wears away even the mightiest mountains to dust.

About Groucho’s memoir Groucho and Me, which gives up being a memoir halfway through and becomes a series of riffs on whatever Groucho is thinking about, there is unfortunately not much to say. Harpo co-wrote Harpo Speaks! with Rowland Barber, a minor writer of the Ring Lardner-Damon Runyon school who knew how to turn a phrase, paint a vivid scene, and give a book a finely realized narrative structure. Groucho employed no such professional assistance. But Harpo Speaks! also makes much of how, while Harpo was a second-grade dropout, Groucho was a child bookworm who would spend much of his free time at the library. He considered himself a bit of a writer throughout his life, loved Henry James and Somerset Maugham, and even carried on a somewhat wary correspondence with T.S. Eliot, so I had high hopes for the literary quality of Groucho and Me. Unfortunately, it is hamstrung by Groucho’s extreme reluctance to reveal anything of himself or his private life, preferring to diffuse everything into a joke and write short riffs on such horridly typical rich-celebrity subjects as fishing, sex, and golf. These jokes can be funny, but over 278 pages they begin to have a wearying effect, and the aging Groucho lacks the rapid-fire bebop surrealism of his younger self. Occasionally, it becomes a thing heartbreaking to see from Groucho Marx: the complaints of a tired old man.

It does, however, give the reader an appreciation for the utterly impossible task of biography. It’s rare that one has the chance to read two different books by two brothers who worked together for their entire professional life and shared many of the same experiences, and the differences in interpretation of the same events are enough to turn you into Janet Malcolm. The brothers’ father, Samuel “Frenchie” Marx, is described by Harpo as a gentle soul who could never bring himself to physically punish his children, while Groucho will climax many of his stories of his and Chico’s youthful misadventures with a furious Frenchie administering a beating. An anecdote about hiding jawbreakers under a hat happens to Harpo in Harpo Speaks! and Groucho in Groucho and Me. Perhaps reading Harpo first predisposed me to mistrusting Groucho’s book, but while any biography contains its falsifications and misrememberings, Harpo’s book feels spiritually true, while you get the sense Groucho is just doing schtick, spinning yarns he’s told at a thousand parties.

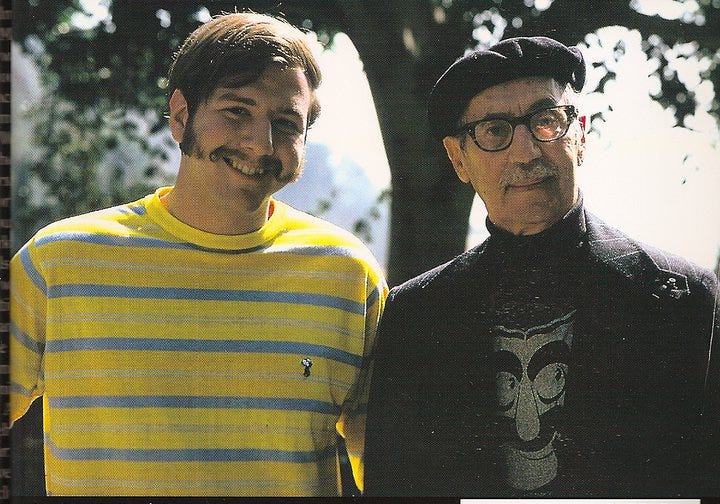

If you do want to read a book about Groucho, there’s always the stranger-than-fiction chronicle of his final years: Raised Eyebrows: My Years Inside Groucho’s House by his former secretary Steve Stoliar. Raised Eyebrows details how Stoliar came to work for his hero, sorting his fan mail and archiving his Hollywood memorabilia. It’s also a key eyewitness document in the most controversial piece of Groucho lore: his relationship with his enigmatic special friend/manager/svengali Erin Fleming.

Fleming entered Groucho’s life in his dotage and became his constant companion (Whether this fifty-year age gap relationship had a sexual element will remain forever a mystery—Stoliar, for the record, doesn’t think so). Depending on who you ask, she either reinvigorated his zest for life or cajoled, abused, and eventually drugged him in an attempt to capture his fortune for herself. Both of these things appear to be somewhat true. Groucho appeared to enjoy being around her and benefited from her youth and energy. She helped contribute to his renewed popularity among the counterculture, got him on talk shows, and made hip Hollywood names like Elliott Gould and Woody Allen fixtures at his home, along with the usual parade of aged vaudeville stars. She was also controlling, mercurial, and mentally unstable, terrorizing Groucho’s staff and demanding that Groucho follow a grueling performance schedule, even after he was diminished by a series of strokes.

Stoliar enters this strange situation as a young, celebrity-mad college student, after helping to persuade Universal to re-release the rarely-seen Animal Crackers, and spends his days trying to get close to Groucho while avoiding Erin’s wrath. If nothing else, the book is a counterbalance to my earlier charge that Groucho had lost his touch, containing as it does many wonderful everyday displays of his humor, though again it must be stressed, the droll one-liners for which he is known are nothing compared to the Joycean fits of divine madness that seem to overtake him in the best films2.

Raised Eyebrows has the gently melancholy feeling of a coming-of-age comedy, which is probably why many directors have been attached to it over the years, though so far to no avail (It has been a dream project of Marx Brothers fanatic Rob Zombie for years—I urge my millionaire readers to fund this!). I feared when I started the book that Stoliar’s fannish nature, his penchant for inserting himself in the lives of his heroes, and his mania for autographs would quickly become tiring. But he is a witty and sensitive narrator, and the book even features a naturally dramatic climax, in which Stoliar puts the lessons he learned from his hero to good use. During the grueling legal battle over Groucho’s conservatorship, instigated by Groucho’s son Arthur after Erin becomes increasingly unhinged, Stoliar is subject to days of interrogation by Erin’s lawyer, but manages to calm his nerves by diffusing the more aggressive questions with Grouchoesque quips and wisecracks:

At one point, on the third day of my grilling, Donahue asked me if I thought that Groucho loved Erin. I started to make a delineation between loving and being in love. I felt that Groucho had been superficially infatuated with Erin, which was more along the lines of being in love, whereas I saw loving as a deeper, more durable feeling that built over a longer period of time.

Donahue said he didn’t understand the difference, and proceeded to set up a hypothetical situation wherein he and I would go out for beers and begin discussing women and dating and love. After he’d spent a couple of minutes setting the scene, I said, “This could never happen.” Puzzled, he said, “Why not?” I answered,“Because I really don’t like beer.”

Donahue blew his top, admonishing me, “Mr. Stoliar, if you would refrain from ad-libbing, we might actually be able to finish this deposition!” I calmly replied, “Mr. Donahue, are you implying that I should prepare my answers ahead of time?”

You’d like the story of a comedian to have a happy ending, but the truth of the circumstances prevent Raised Eyebrows from delivering one. Groucho fades slowly away as Erin and his children battle over his legacy, and Erin slips further into mental illness after his death, eventually surfacing in a bizarre series of court battles, represented by celebrity lawyer Melvin Belli, glassy-eyed, incoherent, and wearing a homemade Groucho sweater, before disappearing again. She died, homeless and adrift, in 2003. Her grave reads “Hello, I Must Be Going.”

Times are tough for America’s trickster heroes. Just this week, Warner Brothers has refused to market a spiritual sibling of the Marx Brothers, the new and lovingly crafted Looney Tunes movie The Day the Earth Blew Up, which was rescued from being unceremoniously shelved only by a new distributor and some complex Hollywood politicking. The same week, instead of taking advantage of the opportunity to promote their own characters, WB removed nearly the entire catalogue of classic Looney Tunes shorts, for my money one of America’s great artistic contributions to the world, from their Max streaming service. Make no mistake, this is a spiritual war! Hollywood studios have never been run by artists (and two cheers for that, I say, having known a lot of artists), but recently, as they attempt to do away with the individual craftsman for good and bring about the age of the machine, they have redoubled their efforts to suppress the anarchic spirit, to put Coyote in a cage. They might accept a company man like Mickey Mouse, but have no time for figures like Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, or Groucho Marx, who suggest even to their young audiences that order, stability, and authority are just temporary bubbles, waiting to be popped. As Blake Smith, paraphrasing Gary Snyder, suggests in a recent essay:

The gods, or muses, or whatever names we might give to the ultimate and inhuman energies at the back of our speech, express themselves in oblique, humorous fashion through state bureaucracies, artifacts of popular culture, and other unwitting agents [...] we are, at least in some moments as writers and readers, already in the paradise of reconciliations, if only we know how to read the book of the world—how to see, as they cast shadows that appear to us as cartoons, propaganda, and other misshapen modern myths, the fresh and ancient gods.

The Marx Brothers always hated people trying to over-intellectualize their comedy, and would insist that they were just kids from the Upper East Side trying to make good. But is it so crazy to say that the reason Groucho, Harpo, and Chico still inspire after nearly a century, which in comedy time may as well be a millennium, is because they tapped into something deep and true in the human spirit that even they didn’t understand? To say that in the honk of a horn and the waggle of an eyebrow, in the irresistible urge to crack wise and cause trouble, you can sometimes catch a glimpse of something wild, strange, and elemental, something that could be the shadowy, grinning figure of Dionysus himself?

I dunno. Honk honk!

Sorry Chico fans: I will be giving Chico short shrift in this essay, partly because he is in the middle of the extremes of silent Harpo and manic talker Groucho and therefore less interesting, and partly because he didn’t write a book.

I like to poke philosophers in the eye as much as the next guy, but Cavell’s essay is genuinely great on this, and worth reading. Typical example, from Monkey Business:

Woman: What brought you here?

Groucho [Dramatically]: Ah, ’tis midsummer madness, the music in my temples ... Kapellmeister, let the violas throb. My regiment leaves at dawn!

Woman: You can’t stay in that closet.

Groucho: Oh, I can’t, can I? That’s what they said to Thomas Edison, mighty inventor, Thomas Lindberg, mighty flyer, and Thomas Shefsky, mighty like a rose. Just remember, my little cabbage, that if there weren’t any closets, there wouldn’t be any hooks, and if there weren’t any hooks, there wouldn’t be any fish, and that would suit me fine.

Thanks for the kindly type words about my book, Raised Eyebrows . Rob Zombie is no longer manning the helm. The Director and writer, with me, is Oren Moverman. Geoffrey Rush is eager to play Groucho. Sienna Miller has agreed to play Erin Fleming. Cold Iron Pictures is overseeing it. We are ready to go, except for that minor snag of funding. so once we have the money, we will get underway. Geoffrey said the good part of all the delays is that he will require less and less make up to play Groucho.

As a committed Marxist I loved this (nice Bloomian American Sublime shoutout too)