Christopher Hitchens had the misfortune of doing all his best work before he became famous and then, just as his work and public persona became stale, boorish, and tiresome, becoming about as famous as a writer can be. This may have coincided with his break with the left, full-throated support for the Iraq War, and reinvention as a figurehead of New Atheism, but don’t think I’m here to do mere ideology critique. Though it’s always difficult to disentangle aesthetics and politics, one can imagine a plausible scenario in which his writing remained interesting even as his political views drifted right1. His essays on literature did maintain their spark, sort of, until the end.

But take a look at some of the horrors on offer in his late collection Arguably. In addition to the usual bluster on Bush’s foreign policy (he’s for it) and religion (he’s against it), a section called “Amusements, Annoyances, and Disappointments” catalogues for posterity such lapidary displays of wit as “Why Women Aren’t Funny,” “As American as Apple Pie,” a piece of profoundly, excruciatingly middle-aged dithering on the phenomenon of the blowjob, and “Wine Drinkers of the World, Unite,” 1500 dismal words on his hatred of overattentive waiters. I don’t care what your politics are, in America, we call that losing your fastball.

So given that the late Hitchens is the one most readers today are familiar with, it makes me feel slightly sheepish to say that the early Hitchens wrote the single literary essay that I have read more times than any other, the one that, to me, exemplifies all the heights and pleasures of the form.

I say sheepish. There is a secret pleasure in it too. I sometimes wonder if I have a special attraction to writers who later in life went to places I would not follow. The tragic hero, after all, is more compelling than the straightforward do-gooder. And it is perhaps a perverse form of chivalry to defend someone’s work against those who would smear their entire corpus based on the received wisdom that proliferates online. While one can’t be bothered to read every crank or reactionary that heaves into view, in certain circumstances it can be a thrill, and an affirmation of your own catholicity of taste to say: I’ve actually done the reading, schmuck. I know of what I speak. Can you say the same?

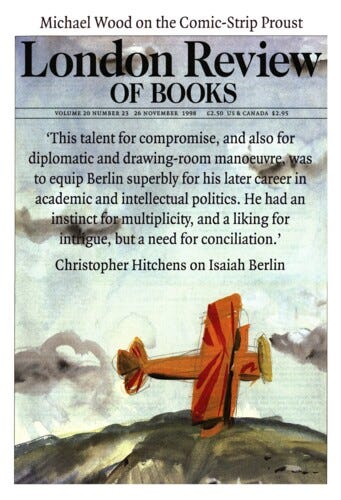

But all of this is throat-clearing in order to gain your trust, so that we, together, can do an exegesis of the aforementioned essay. The essay is called “Moderation or Death,” and appears on the LRB website as well as in the recent collection A Hitch in Time, which is the Hitchens volume to get for the curious (Unacknowledged Legislation, which collects his great literary journalism of the 1990s, is out of print but can be found for pennies online. The massive late collections, which clutter the shelves of used bookstores nationwide, can be skipped.). It’s 13,000 words and will take you most of a lunch hour to read, but I really do recommend taking the time.

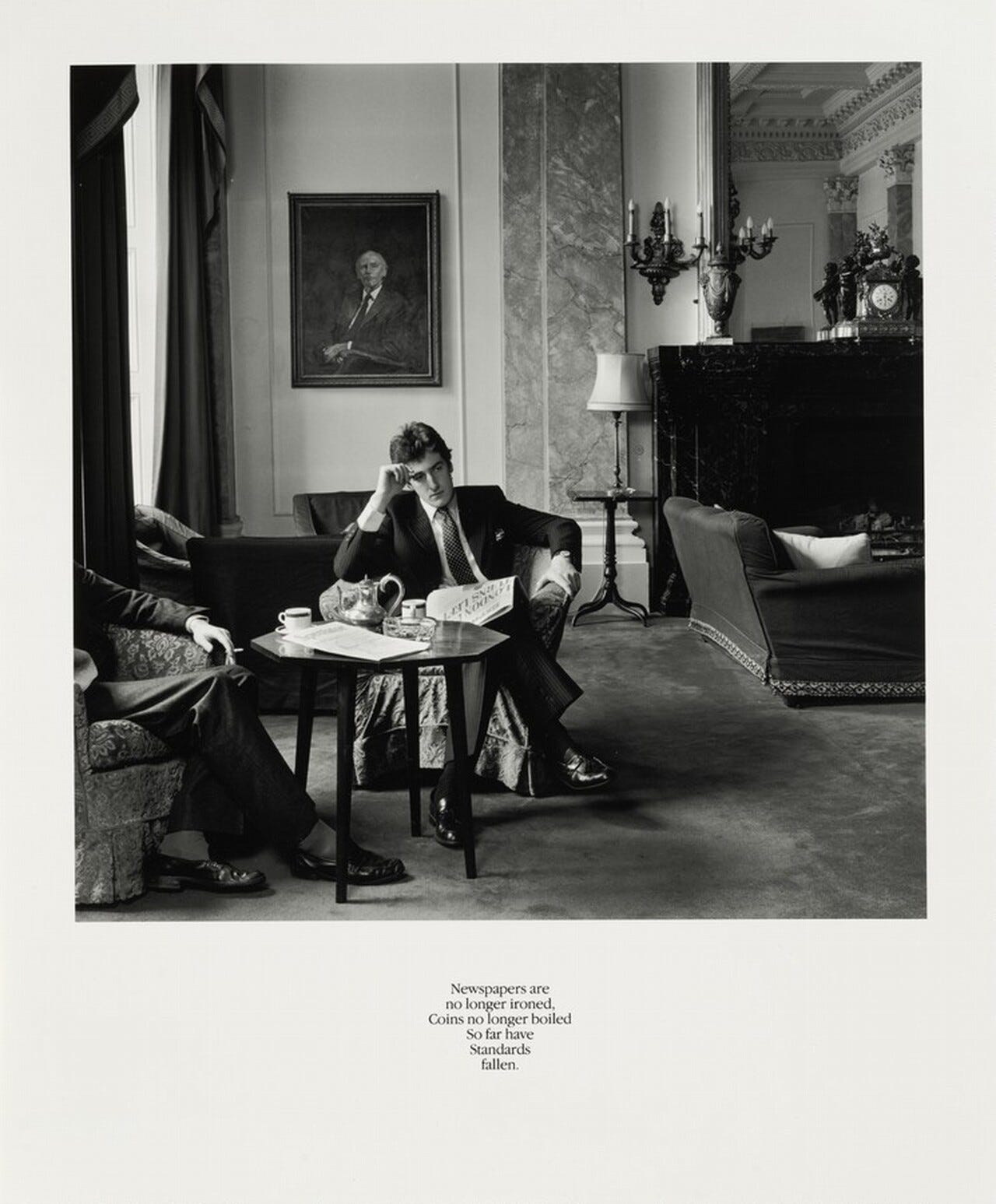

Ostensibly a review of Michael Ignatieff’s 1998 biography of Isaiah Berlin, “Moderation or Death” is in reality a long, devastating poison pen letter to the late Berlin, alternating mostly affectionate personal recollections with the presentation of damning evidence, as well as a larger attack on the figure of the court intellectual in general, who strives to “find a high ‘liberal’ justification either for the status quo or for the immediate needs of the conservative authorities.” But really what it is is a performance of pure style. When one thinks of the great essays of the twentieth century—“Shooting an Elephant,” say, or “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”—one tends to think of concision, understatement, implication, the right word in the right place, the right thought clearly expressed. “Moderation or Death” is like something pulled out of the eighteenth or nineteenth century, a great coffeehouse blusterer like Johnson or Hazlitt, operating by force and accumulation rather than subtlety, swinging the axe wildly rather than placing the arrow between the eyes. But it is no less brilliant for it and to someone like me, raised on the former style rather than the latter, it was a revelation.

It begins by invoking Berlin’s friendship with the “dynastic technocrats who organised and justified the hideous war in Vietnam,” quoting an obsequious letter from Berlin to one of said Cold Warriors, and continuing:

As an ever-increasing number even of Establishment types began to sicken of the war, Alsop reflected bitterly that he might no longer be able to claim the standing of stern prophet and moral tutor to the military-industrial (and military-intellectual) complex. Berlin responded in the same tones of seasoned statesmanship:

“I can see the thin red line, formed by you and Mac and me, and Chip Bohlen – four old blimps, the last defenders of a dry, and disagreeably pessimistic, tough and hopelessly outmoded position – one will perish at least with one’s eyes open.”

‘Take my arm, old toad. Help me down Cemetery Road.’ Except that it was actually many thousands of conscripted Americans, and uncountable numbers of Vietnamese, and not the intellectuals at the elbow of power, who were marched down that road before their time. Almost everything is wrong with the tone and address of the above extracts: the combined ingratiation and self-pity no less than the assumed and bogus Late Roman stoicism. A ‘terrific domino man’ indeed! What price ‘negative liberty’ now? And what of the sceptical humanist who warned incessantly about the sacrifice of living people to abstract ends, or totemic dogmas?

Effective stuff (though tragic ironies abound—no reader of Late Hitchens will fail to recognize the parallel between Berlin’s cozy relationship with these types and Hitchens’s own praise for Paul Wolfowitz and company). One very useful thing Hitchens, among others, taught me is that you don’t actually need to hold anyone’s hand when doing the old high-low register shuffle. Unlike, say, present-day criticism in the New York Times that insists on clarifying that Paradise Lost is a 1667 poem by John Milton2, Hitchens can just drop a relatively lesser-known line of Larkin in there with no clarification before moving on, and it doesn’t read as willfully obscurantist because, whether you know the reference or not, the tone of withering contempt comes through. In fact, there are passages of “Moderation or Death” that are quite dizzying and difficult on first read, not difficult in the hierophantic manner of a Jameson or an Adorno, but in their chaotic whirl of pub talk, historical allusion, barbed aside, name-dropping, and personal recollection.

I should say here that to this day I know next to nothing about Berlin; the extent of my knowledge going into this essay was that he wrote a book on Russian writers that I vaguely intend to read someday, and his famous essay on the Hedgehog and the Fox, which I know as one of those snappy phrases or concepts to which towering intellects are reduced in one’s memory palace: “hard, gemlike flame,” “I refute it thus,” “the medium is the message,” and so on. So it could be that Hitchens is being unfair, omitting details of Berlin’s life that clash with his portrait of a complacent toady. But frankly, that doesn’t really matter to me. The performance is the thing.

We go on. Hitchens recalls Berlin’s kindness to him as an Oxford undergraduate. He notes that the biography reveals that Berlin did in fact deliberately ruin the career of the Marxist historian Isaac Deutscher, an allegation Berlin denied to Hitchens’s face. He pounds Berlin from every angle. There’s the psychological: did Berlin’s aversion to “disturbance to the natural order” come from an early memory of a tsarist cop beaten by a Bolshevik mob? The genealogical: Berlin’s mixed feelings towards his own Jewish heritage, and his willingness to both level and downplay accusations of anti-semitism, depending on whether the accused in question could help his career. The scholarly: Hitchens digs up an old academic paper comparing two separate versions of Four Essays on Liberty, and reveals Berlin’s habit of swapping in the name of one great thinker for another—whether it’s Hobbes or Spinoza or Aquinas, they all turn out “to confirm in the first place one another and in the second place whatever he was going to say anyway.”

One pauses to note that this essay was written in 1998, before every academic journal and magazine in the world could be brought up with the touch of a button, and its collage of citation, anecdote, memory, and reference would have required not only a lifetime of serious intellectual engagement just as a baseline, but considerably more menial effort than it would have taken even five or ten years later. When faced with such a heroic example, the laziness of much writing on the internet becomes all the more dispiriting and it compels one to do right by Hitchens’s example, and take better advantage of the wondrous resources at our command. And I don’t think the London Review of Books was paying Vanity Fair money, even for a marquee piece like this. It’s sheer passion, and sheer love of the discourse. We should all take inspiration.

The essay continues. One feels it could just go on and on forever, an endless list of incidents of pusillanimity and hypocrisy. By its end, Berlin has been dissected and put back together, held up to the light, rotated 360 degrees, examined for every flaw, and finally dismissed with a wave of the hand as a “skilled ventriloquist,” his image as an important twentieth century thinker having been, for anyone who reaches the end of “Moderation or Death,” badly cracked if not damaged irreparably.

But there is limited virtue in being a mere takedown artist. What also gives this essay life is the note of sympathy, understanding, even love sounded throughout for Berlin. Even as Hitchens takes a hatchet to his reputation, he builds Berlin up as a great, novelistic character, wanting more for himself than to be an “intellectual taxicab” for the architects of Empire, but too cowardly to ever break away from his masters.

Isaiah Berlin may have been designed, by origin and by temperament and by life experience, to become one of those witty and accomplished valets du pouvoir who adorn, and even raise the tone of, the better class of court. But there was something in him that recognised this as an ignoble and insufficient aspiration, and impelled him to resist it where he dared.

(Later:)

I propose that Berlin was somewhat haunted, all of his life, by the need to please and conciliate others; a need which in some people is base but which also happened to engage his most attractive and ebullient talents. I further propose that he sometimes felt or saw the need to be courageous, but usually – oh dear – at just the same moment that he remembered an urgent appointment elsewhere.

It’s all in that early anecdote of young Hitchens meeting Berlin at Oxford, I think.

He’d agreed to talk on Marx, and to be given dinner at the Union beforehand, and he was the very picture of patient, non-condescending charm [...] He gave his personal reasons for opposing Marxism (‘I saw the revolution in St Petersburg, and it quite cured me for life. Cured me for life’) and I remember thinking that I’d never before met anyone who had a real-time memory of 1917. [...] A term or two later, at a cocktail party given by my tutor, he remembered our dinner, remembered my name without making a patronising show of it, and stayed to tell a good story about Christopher Hill and John Sparrow…

This sense of the jilted admirer, of the inevitable experience of getting older and wiser and realizing the essential frailty and pathetic qualities of so many adults in general, much less intellectuals, pulses in the background of “Moderation or Death.” It gives it a Dostoevskian pathos, the poignancy of the son turning on the father. And that, in the end, is why I consider it such a landmark of a form—literary journalism—that is generally such a minor art. Here is great human drama, one of many stories of seduction and betrayal in twentieth century intellectual life—a domain in which there really was a lot at stake—expressed by a major stylist. Its effects are as vivid and powerful as a novel.

Eventually, Hitchens in his turn became the betrayer. His longing for a cause, like the ones his hero Orwell found in Spain and in the Second World War, led him to support and doggedly defend the Iraq debacle, well after other liberals and even some conservatives jumped ship. And “New Atheist” is now all but a dirty word, its greatest legacies are a renewed interest in the spiritual and the numinous among the young and the cringeworthy debate culture one finds on Twitch and YouTube. I’d like to remember him as the essayist who wrote so well on Wilde and Wodehouse and Kipling, and who spat brilliant venom on bad characters like Henry Kissinger. But one must admit that his project as a whole was a failure, that his self-declared mission to be the Orwell of his times—to be the lonely voice that stood for good English common sense independent of ideology—foundered and sank.

Stefan Collini, when the LRB dispatched him to bring down their wayward son, had this to say in tribute to Hitchens; a few honeyed words before he drew the dagger from the toga:

It’s worth considering what kind of cultural authority this type of writing can lay claim to these days. It self-consciously repudiates the credentials of academic scholarship; it disparages the narrow technical expertise of the policy wonk; it cannot rest on the standing of achievement as a politician or novelist. In other words, it has nothing to declare but its talent. Knowing the facts is very important; knowing the people helps (there’s a fair bit of anecdotage and I-was-there-ism in Hitchens’s journalism). But in the end it stands or falls by the cogency of its case, based on vigorous moral intuitions, honesty and integrity in expressing them, mastery of the relevant sources and a forceful, readable style. Car licence-plates in New Hampshire bear (rather threateningly, it always seems to me, as big SUVs speed by) the state motto ‘Live free or die.’ In this spirit, the maxim on Hitchens’s crest has to be ‘Get it right or die.’

There is the spirit I still respect, as a fellow writer affiliated with no institution or ideology. To go out there without a net, to rise or fall by talent alone, to speak directly to the public with wit and verve and smoky, sotted romance—I can’t think of a more thrilling way to do it. Though I recognize and respect those who toil in said institutions, and often wish I had the patience and mental ability to work my way more systematically through problems of philosophy and politics, style, integrity, and moral instinct will always, for me, be the reason to play the game in the first place. This can be a dangerous road to travel (don’t look up his best friend Martin Amis’s post 9/11 comments, either!) and the sense that you’re the only sane man in an insane world can lead that moral instinct into disaster. It led Hitchens into bleak self-parody, in the end. But the heights—oh, God, what heights!

The New Atheist routine, in which he played an American’s idea of a sozzled English rogue in debates with featherweight targets like Dinesh D’Souza and Rabbi Shmuley, was probably doomed from the start.

h/t BDM’s essay on this kind of writing for this example, to which I have also returned several times. A tip of the hat also to this piece by Robert Fay, which got me thinking about the Berlin essay again, though Fay is decidedly more a fan of the Late Hitch than I.

I enjoyed this a lot. But if you ever call Samuel Johnson a blusterer again the King’s Government will send someone to find you and extract a written apology.

I gave his blowjob essay a reread recently on a whim and I've never been sadder to have brain on the brain. That thing is so balls, man. If you think "brain on the brain" is bad, check his wordplay in that one.

Still. I revered Hitchens more than Amis for a long time because even with his florid style and tub-thumping he never left me feeling inert. As you say: "The performance is the thing." The erudition is wild and his pronouncements great bait for dorks and pedants; I love it. He made me want to think and want to write. Amis on the other hand could put me in a state of paralytic admiration. What's the line in The Information? "When he reviewed a book it stayed reviewed." Unfortunately, Amis also put it best about Hitchens: "He made intellection feel daring."

Side note: Hitchens feels like the sort of semi-maximalist that I can get behind. Info out the wazoo, a whipping live-wire intensity, unexplained allusions and logical elusions, a feeling of genuine, clumsy, and giddying immensity--these are the things I don't get from some of the partisans of big style. Good things are good and bad things are bad, etc., and this is the good thing I like. Some kids just play better than others. It helps that, ignoring the blowjob essay, and a few others, Hitchens could actually be funny, and even if brevity is the soul of wit a good sense of humor always feels like expansion.

Would love to see you treat Hitchens at even greater length in the future. I feel like you could give the corpus a fair shake.