Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes by Stephen Sondheim

(with help from Let’s Do It: The Birth of Pop Music – A History by Bob Stanley)

People looking to disparage modern literature will often complain that it has changed from an art to a craft. Gone are the days, they say, when writers considered themselves attuned to some outside force, mere channels for the muse, the antennae of the race. Now our novelists and poets consider themselves dutiful little craftsmen, attending Iowa or Columbia or NYU to learn from masters of the trade and going into the world to hammer out finely wrought but uninspired work, losing the wild vitality that animated the romantics and modernists.

Though this is a vast oversimplification, a half-truth at best, a half-truth is still a some-truth. So it is curious to consider that as literature underwent this shift, popular music was transforming in the opposite direction. While modern pop music is the product of many artisans, these days it’s hard to shake off appraising it with a Romantic sensibility; as the uncontaminated expression of one artistic soul. And this is true on all levels, from bedroom producers and coffeehouse strummers to Taylor Swift, whose records involve dozens of producers, co-writers, and musicians, but who is read by her fans on a diaristic, personal level, as though she were Sylvia Plath1.

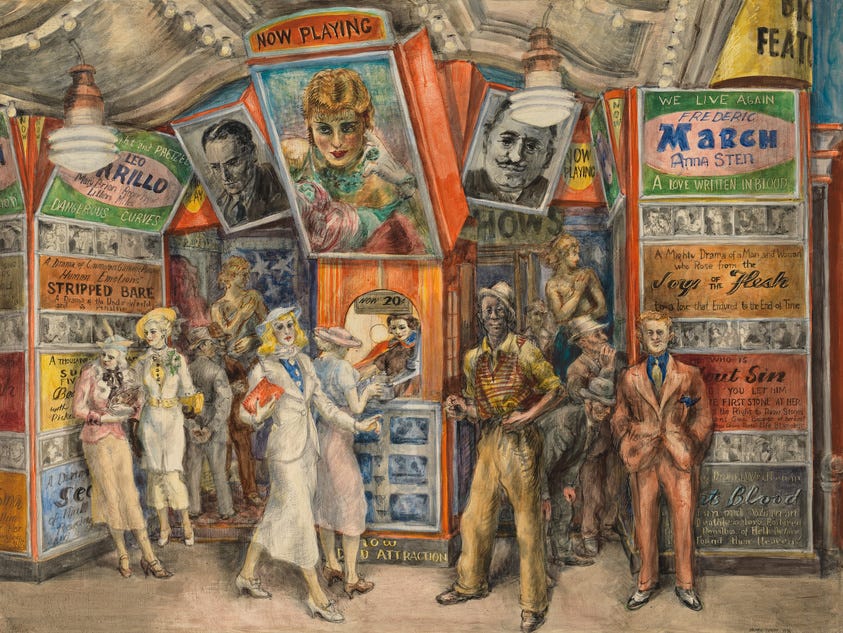

But there was a time, from around the invention of the Gramophone to the late 1950s, when popular music was understood as crafted, by people like Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, George and Ira Gershwin, and Cole Porter, who would, figuratively if not literally, clock in to an office, roll up their sleeves, and get to work producing songs, most of which were written for musical theatre but which quickly passed into culture via other recordings, often before the shows even closed. This meant that for the first fifty years of pop’s existence, songs were divorced from singers, they were uniquely free-floating and open to interpretation2. Hear “Creep” and you think Radiohead, hear “Yesterday” and you think The Beatles, hear “All the Things You Are” and you think – who? Maybe Frank Sinatra, maybe Ella Fitzgerald, maybe John Coltrane, but almost certainly not the forgotten 1939 musical Very Warm for May.

Which brings me to Finishing the Hat, the annotated lyrics, partial autobiography, and opinionated consideration of his predecessors by Stephen Sondheim, the most important theatrical composer and lyricist of the twentieth century’s second half. Like Keith Johnstone’s Impro, which I’ve also written about in these pages, Finishing the Hat is a book seemingly concerning a narrow and oft-maligned branch of theatrical practice that will actually be useful, even revelatory, to anyone involved in any creative pursuit at all. Sondheim says it himself in the indispensable introduction:

The explication of any craft, when articulated by an experienced practitioner, can be not only intriguing but also valuable, no matter what particularity the reader may be attracted to. For example, I don't cook, nor do I want to, but I read cooking columns with intense and explicit interest. The technical details echo those which challenge a songwriter: timing, balance, form, surface versus substance, and all the rest of it. They resonate for me even though I have no desire to braise, parboil or sauté. Similarly, I hope, the specific techniques of lyric-writing will enlighten the cook who reads these pages. Choices, decisions and mistakes in every attempt to make something that wasn't there before are essentially the same, and exploring one set of them, I like to believe, may cast light on another.

It would have been easy to dash off a preface to this book, let the editors arrange the lyrics as they saw fit, and call it a day, but Sondheim, ever the perfectionist, cannot abide the thought. Each set of lyrics is given a long introduction describing the genesis of the production they were written for and then intensely annotated, with ruthless honesty in pointing out what he considers his mistakes, failures, and sloppiness. And interspersed throughout are short essays commentating on his predecessors, the men and women who created the form and canon of American song.

So what is the task of the lyricist, according to Sondheim? It is not the same as the task of the poet, who depends on density and evocation rather than clarity and catchiness (he scorns lyrics by poets like W.H. Auden and Langston Hughes who ventured into theatre, saying they “convey the aura of a royal visit”). Mostly, it’s to get out of your own way. The lyricist must serve both the music and the performer by being easy to sing, comprehensible, and not too overwrought, all while managing to convey the emotional tenor of the song. Despite his work’s reputation for being musically complex and somewhat chilly, on the page Sondheim’s lyrics read as quite simple and straightforward, without a word out of place. And contrary to what the Romantic might assume, he is adamant that attention to craft and detail helps to highlight the emotion of the song rather than smother it, as he writes in his extended defense of the importance of true rhyme (as opposed to near rhyme or slant rhyme).

In fact, pop listeners are suspicious of perfect rhymes, associating neatness with a stifling traditionalism and sloppy rhyming with emotional directness and the defiance of restrictions. [...]The notion that good rhymes and the expression of emotion are contradictory qualities, that neatness equals lifelessness is, to borrow a disapproving phrase from my old counterpoint text, "the refuge of the destitute." Claiming that true rhyme is the enemy of substance is the sustaining excuse of lyricists who are unable to rhyme well with any consistency.

"If the craft gets in the way of the feelings, then I'll take the feelings any day." The point which [the unnamed pop star he is criticizing] overlooks is that the craft is supposed to serve the feeling. A good lyric should not only have something to say but a way of saying it as clearly and forcefully as possible—and that involves rhyming cleanly. A perfect rhyme can make a mediocre line bright and a good one brilliant. A near rhyme only dampens the impact.

Then there’s trying to be too clever, and showing off – a common sin. Here’s the rapture of a critic praising the work of Jerome Kern and his partners Guy Bolton and P.G. Wodehouse (yes, that P.G. Wodehouse), as cited in Bob Stanley’s book Let’s Do It.

Nobody knows what on earth they’ve been bitten by

All I can say is I mean to get lit an’ buy

Orchestra seats for the next one that’s written by

Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern

Not to dig up this long-dead man’s tossed-off verse just to bury it, but recite it and you can see that, despite the superficial cleverness of the rhyme, the third line causes the tongue to trip over itself, the glide from “orchestra” to “seats” is difficult, not to mention the dreadful “next one that’s”. Now compare Cole Porter in the bridge of “Anything Goes,” using the same technique of rhyming the penultimate word while repeating the final one:

The world has gone mad today

And good's bad today,

And black's white today,

And day's night today,

When most guys today

That women prize today

Are just silly gigolos

Mad/bad, white/night, guys/prize – these are as elementary and obvious as it gets, but the recitation could not be sprightlier or easier on the tongue, and this, combined with the music, gives Porter his reputation for effortless wit and elegance rather than labored cleverness.

An aside: I should say that – and you won’t believe this but I swear it’s true – I actually have fairly little interest in musical theatre. I haven’t seen most of the shows described in Finishing the Hat and what affection I might have for the form is generally compromised by its cringier qualities. Truth be told, while I’m happy to listen to Chet Baker or Ella Fitzgerald or even croaky old Bob Dylan singing this stuff, my aesthetic sensibilities generally can’t make the leap to the originals, with their sickly-sweet orchestration and affected Broadway Voice3. And as for modern examples of the form like Wicked or Hamilton, forget about it. But you’d have to be crazy not to recognize the unbelievable talent that coalesced around composing popular and theatrical song in the first half of the century. It’s like the peak of classic Hollywood, the Elizabethan stage, or the golden era of Looney Tunes – a marriage of artistic sensibilities and urgent commercial needs that kept a coterie of talented craftsmen churning out masterpieces at an accelerated rate.

The funny thing about Sondheim is that, for all his genius, he represents the final closing of the door on the era that I love. Let me try to explain why. Sondheim’s mentor was the lyricist Oscar Hammerstein, who with his composing partner Richard Rodgers helped to inaugurate the golden age of the American musical. When you think of the form, it’s Rodgers and Hammerstein shows – Oklahoma!, South Pacific, The King and I, The Sound of Music – that come to mind. While most previous musicals used a throwaway plot filled with light comedy as an excuse to get to the songs, Rodgers and Hammerstein were the first to fully integrate dance, music, and dialogue, which is why you, the reader, have heard of the plays in the sentence above and haven’t heard of plays like Fifty Million Frenchmen, DuBarry Was a Lady, or Lew Leslie's International Revue, despite perhaps having heard songs that originated in them. Hammerstein’s maxim was “The song is the servant of the play.” This made their shows mature, integrated works of art that are still performed today, but in doing so the songs became thickly attached to the play instead of thinly attached. Belonging to the show they were written for, they ceased to belong to everyone.

Sondheim’s work takes Hammerstein’s innovations and builds on them. His songs are complex and dialogic, often avoiding the familiar thirty-two bar solo or duet structure in favor of something more polyphonic and angular, without discernible verse, chorus, or bridge. They are often difficult to hum or immediately recall, and they expand far outward from Hammerstein’s cornball emoting to encompass more ambivalent, complicated, and cynical emotional territory. For all their brilliance, there is something hermetic about them. Whether the advent of rock music and the auteur mode of songwriting actively killed the old model of pop or simply took advantage of an already-existing void is a matter for historians to debate4. But in either case, Sondheim’s work is the sound of musical theatre coming into its own but also withdrawing into itself, becoming a specialty art form rather than a populist one.

It’s illustrative to look at Sondheim's take on Rodgers’ pre-Hammerstein songwriting partner, Lorenz Hart, who I have avoided mentioning until now. Of all the songwriters and composers of this era, I find Hart’s work with Rodgers, in songs like “Blue Moon,” “My Funny Valentine,” “Manhattan,” and “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” the most sensitive, witty, melancholy, and vulnerable. Barely five feet tall, looks-wise not exactly a matinee idol, an alcoholic, and a closeted homosexual, Hart’s songs are shot through with a deep wistfulness, the perspective of a man who never quite felt at home in the world (and indeed, his alcoholism claimed him just a few months after the premiere of his replacement’s debut show Oklahoma!). So I was surprised to find that Sondheim is rather vicious towards Hart, calling him “the laziest of the pre-eminent lyricists,” accusing him of squandering his talents, and taking him to task for all manner of sloppy rhymes and egregious mis-stresses. On the line "Your looks are laughable/unphotographable," from "My Funny Valentine," he sneers: “Unless the object of the singer's affection is a vampire, surely what Hart means is ‘unphotogenic.’” While Sondheim’s technical rigor is what makes the book worth reading in the first place, this is where we part ways: for me, there does come a time when artistry makes questions of craft irrelevant, and this sad, brilliant man’s wry encomium to himself is one of them.

But even Sondheim, the master technician, recognizes some essential mystery of music. When discussing “Send in the Clowns,” the only song of his that achieved widespread recognition as a standard, he confesses he has no idea why this, of all the ballads he’s written, became so popular and widely recorded. And listening to the song, it’s hard to pinpoint anything. Shorn of context, the lyrics don’t make much sense, and it’s difficult to tell what the song is even about. Yet somehow, the sense of missed opportunity and the rueful recognition of life’s absurdities comes through, propelled by a higher intelligence than is easily diagrammable. At the end of the day, you can go very far approaching it as a craftsman, but music is the supreme mystery, the closest thing to an encounter with the divine most of us will ever have. It simply doesn’t make sense that an arrangement of sounds has the power to provoke such intense and varied emotions, and yet it persists in doing so.

Maybe you still aren’t convinced that you could get something out of Finishing the Hat. In that case, I’ll just leave you with the very first page of the book, in which Sondheim lays out his three principles, necessary for a lyricist according to him, but really essential for writers and artists of any kind. They are as follows:

Content Dictates Form

Less Is More

God Is in the Details

all in the service of

Clarity

As Ira Gershwin once wrote: who could ask for anything more?

A funny example of this sort of misunderstanding of the role of the singer came in the filming of one of the recent Star Trek shows, which contained a scene in which one of the characters was supposed to sing “Feeling Good.” But the actress, drunk on 2021-era Hollywood sanctimony, demurred, feeling that it would not be appropriate for a white woman to sing because of Nina Simone’s famous interpretation of the song as an anthem for the Civil Rights movement. Of course, “Feeling Good,” was written by two white Englishmen for a now long-forgotten musical about the class system, and by the time Nina Simone got to it, had already been sung by dozens of different artists.

I discovered the Great American Songbook (as it is called) through jazz, a common trap. First your cuttingly hip interest in avant-garde, spiritual music draws you to Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders, then you’re listening to Miles Davis doing “My Funny Valentine,” then you start to wonder where all these jazz standards came from, anyway, and suddenly you find yourself listening to something that makes you feel like you should be wearing a fedora and smoking a cigarette in a holder.

Incidentally, as annoying as it is when boomers go on and on about The Beatles, taking the century-long view of pop music leaves you unable to deny their seismic influence. Lennon and McCartney are the point at which the pendulum definitively swings from craft to art, where song and singer become inseparable, for better or for worse.

I love this exploration of songwriting. Rodgers and Hart songs are some of my favorites. Sondheim's great, but he's such a snob. Unphotogenic indeed. GTFO. As an avid, rhyming lyricist, I'm glad to read an exploration of the difference between lyric and poetry. I would add that lyrics are intertwined with music, while poetry is crafted to stand on its own. This is why I never submit to any lyrics contest. To continue with Sondheim's comparison, it's like submitting ingredients to a cooking contest.

I adore Sondheim and treasure these books but absolutely agree with your take. I'll only add that his inclinations as a songwriter, towards complexity and dialogic as you said, have an even more deleterious effect upon his dramaturgy.

His instincts just do not align with an effective structure of the dramatic story. Into the Woods, Merrily We Roll Along, and Sunday in the Park with George serve as particularly glaring examples of musicals whose neatly complex structure, ambivalent, complicated and cynical, absolutely undercut any satisfying dramatic experience for the audience, even when made up of several hummable songs. Sondheim isn't a book-writer per se, but surely most be held responsible for these type of story structures. I'd argue Being Alive and Send in the Clowns are exceptions that prove the rule, where a slightly more traditional story structure imbues those songs with an emotional heft that carries the audience through some of the exactitude of the songwriting. It's not for nothing that many of the most beloved Sondheim songs are First-Act'ers...though he's certainly not the only writer to struggle here.

Wonderful review and an instant subscribe from me.