“Either kill me,” said the Marquis de Sade, “or take me as I am, for I shall never change,” and such a declaration could have been made just as easily by Norman Mailer, dead now these eighteen years and fading fast, yesterday’s man, a memory, a phantasmagorical embodiment of all that was misguided about white American men who wrote literature in the twentieth century, a man who in his quest to become something he was incapable of becoming— the Great American Writer— left behind a trail of wrecked relationships, ruined lives, and even real corpses. Or so said the reigning conventional wisdom. For all I knew, perhaps he better resembled another catalogue of traits, his own self-description from The Armies of the Night:

“a warrior, presumptive general, ex-political candidate, embattled aging enfant terrible of the literary world, wise father of six children, radical intellectual, existential philosopher, hard-working author, champion of obscenity, husband of four battling sweet wives, amiable bar drinker, and much exaggerated street fighter, party giver, hostess insulter…”

Whatever the case, I knew I would have to come to Mailer eventually and decide for myself, given both the recent Nixon-style electoral backlash and the recent flare-ups of discourse about the male ego and its place in literary fiction, the men on their back foot this time, Vivian Gornick’s 1976 essay “Why Do These Men Hate Women?,” about the failings of Mailer, Roth, and Bellow, having gone from cry in the wilderness to duly received wisdom. With respect to Gornick’s incisive and often correct appraisal, I find myself incapable of losing my reverence for the latter two; for better or for worse they helped teach me what a novel could do. Roth I discovered at a young age, and while I was taking a prurient adolescent interest in the more pungent moments of Portnoy’s Complaint and The Plot Against America I now realize that deep in the reaches of my subconscious I was being taught what great writing was. Bellow I had foolishly dismissed as of historical interest only, when I picked him up last year it was like being hit in the face with a 2x4. So Mailer loomed, a problem, a pugnacious little gremlin. His Marvel Cinematic Universe-esque cameo appearance in the back pages of Making It as the link between an old generation of intellectuals and a newer, groovier one (covered in part one of this essay) sealed it. I would have to see what he was all about.

What I discovered in The Armies of the Night was a writer whose commitment to his own boorishness, to putting all of himself on the page and apologizing to no one, makes him often grating but also gives him a folk-hero aura; he seems larger than life in a way none of his contemporaries can equal, and their base impulses and bad behavior seem petty by comparison. Had he lived in the nineteenth century, one feels, mining camps and railroad crews might have swapped stories of Mailer stopping by their campfires on a moonless night and consuming a hundred flapjacks and six quarts of whiskey before felling a mighty redwood with one swing. The Armies of the Night, an epic piece of documentary fiction that solidified his reputation as one of the great New Journalists (at the expense, perhaps, of the great novel he would never write), plunks this colorful figure, referred to throughout in the third person as “Norman Mailer,” at the crisis point of a changing culture, into what will later become a defining piece of hey-man-remember-the-Sixties documentary bait: the 1967 March on the Pentagon.

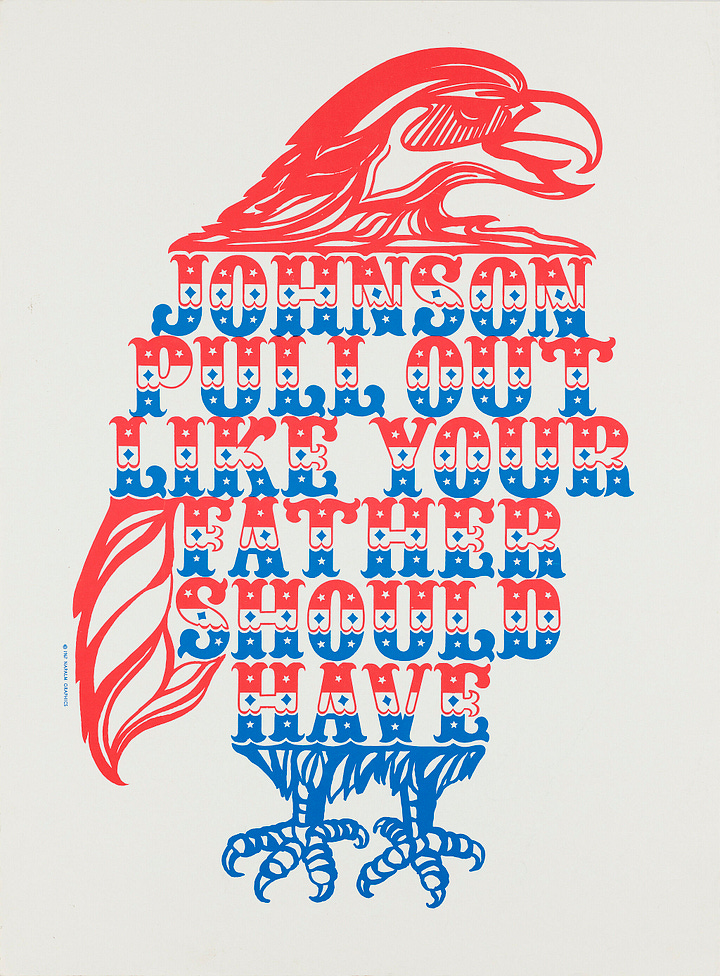

Mailer, 44 years old at the time of writing, was an ideal figure to document this event. He was raised in the Partisan Review Old Left (exemplified by his two companions on the march, Robert Lowell and Dwight MacDonald) and yet shared many of the sensibilities of the New: a distaste for sober theorizing and an attraction to instinct, spontaneity, and the thing-in-itself. Thus the early sections of The Armies of the Night, before the march begins, find Mailer in revolt against his tasteful surroundings. Asked to give a speech at a gathering of wealthy liberals, he makes a drunken spectacle of himself, stalking about the stage with a coffee cup full of bourbon, heckling the audience in a torrent of four-letter-words and goofily dated hipster jive talk. Like Falstaff, his unapologetic oafishness becomes a strangely admirable vitality, though one principle of Mailer Thought has aged quite poorly: his faith in obscenity as a revolutionary and aesthetic principle.

There was no villainy in obscenity for him, just—paradoxically, characteristically—his love for America [...] the noble common man was obscene as an old goat, and his obscenity was what saved him. The sanity of said common democratic man was in his humor, his humor was in his obscenity.

Mailer and his cohort, and the more sweeping set of social changes that followed them, helped break the power of obscenity, yes, but at what cost? Those related to sexual and bodily matters have become cutesy, signifying only the most surface-level and unthreatening faux-rebellion, the apotheosis of Redditism, and the only taboos left to break are those rightfully upheld around derogatory words for groups of people. This is probably an acceptable equilibrium for the most part—one thinks of the middle ages, when you could keep an address on “Gropecunt Lane” but get put in the stocks for exclaiming “God’s wounds!”—but perhaps a problem given the inevitable emergence of some sort of rebellious attitude and iconoclastic impulse among the young.

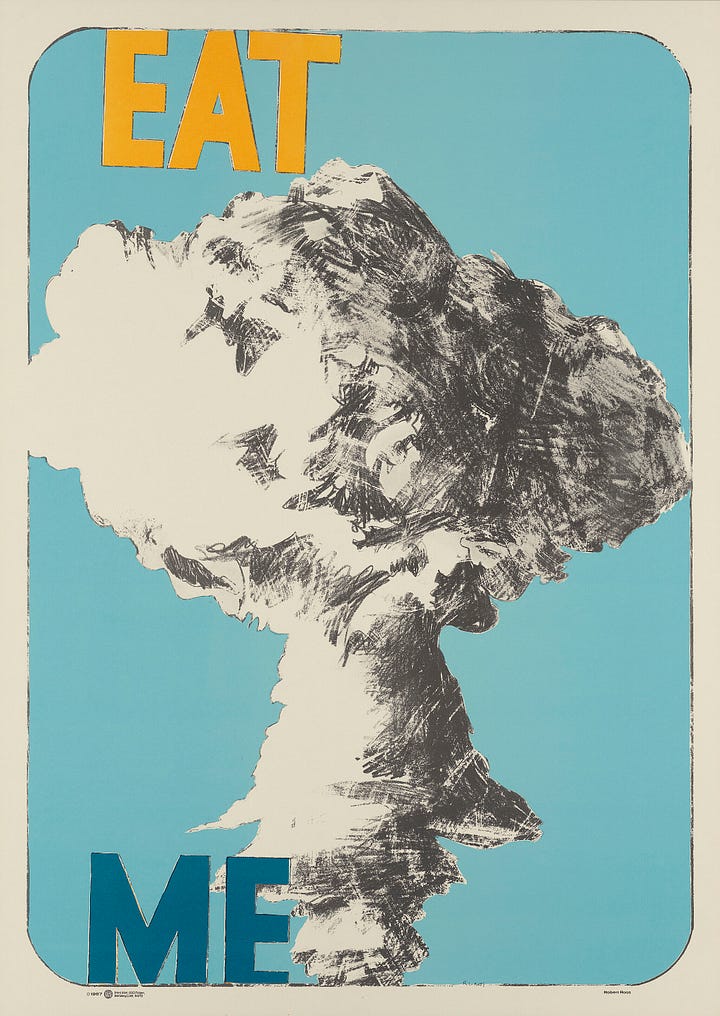

The morning after, when the march begins in earnest, the book becomes a panoramic tour of its participants, the promised “History as a Novel,” rambling lively and sympathetic among the young radicals, the old Reds, and the representatives of Uncle Sam sent to keep order. Among the many picaresque sections, from a speech by Malcolm X’s sister to a face-off in the back of a paddy wagon between Mailer and a neo-Nazi, one encounter is worth noting in particular: Mailer’s account of the famous “Exorcism of the Pentagon,” a mass ritual in which a group of hippies led by Abbie Hoffman and Ed Sanders claimed that the building would “turn orange and vibrate until all evil emissions had fled this levitation,” at which point “the war in Vietnam would end.” Mailer’s companions Lowell, “that personification of ivy climbing a column,” and Macdonald, who “hated meaninglessness even more than the war in Vietnam” find the whole ritual pointless, while Mailer finds this return to the pagan, even if couched in an avant-garde irony, invigorating.

Now, here, after several years of the blandest reports from the religious explorers of LSD, vague Tibetan lama goody-goodness auras of religiosity being the only publicly announced or even rumored fruit from all trips back from the buried Atlantis of LSD, now suddenly an entire generation of acid-heads seemed to have said goodbye to easy visions of heaven, no, now the witches were here, and rites of exorcism, and black terrors of the night…

And Mailer is right, of course, though street theater is not nearly enough to change the world, what is it we remember from this era of protest? Few of the specific speeches, but many iconic performances and happenings (including the attempted levitation itself). In a certain sense The Armies of the Night is an instinctual and attuned writer’s attempt to reckon with the fact that the written word, so precious to Mailer’s fellow Jewish intellectuals, the people of the book, was losing its primacy among the youth in favor of the gesture, the chant, the song, and the action, and that to the sensitive antennae, the first glimmerings of a largely post-literate society were beginning to show.

But besides as a staging ground for rituals such as these, what is the function of mass protest, anyway? Mailer is conflicted. In the mostly rather dry second section of the book “The Novel as History,” in which Mailer leaves his fictional self behind to give a more sober and “factual” (a fraught word, but…) accounting of the events of the weekend, there is a fascinating account of the delicate negotiations between the protest leaders and the Pentagon carried out in advance, and their quibbles over the rally’s location and scope:

It was to a degree incredible, as every paradigm of the twentieth century is incredible. Originally the demonstrators were saying in effect: our country is engaged in a war so hideous that we, in the greatest numbers possible, are going to break the laws of assembly in order to protest this impossible war. The government was saying: this is a war necessary to maintain the very security of this nation, but because of our tradition of free speech and dissent, we will permit your protest, but only if it is orderly. Since these incompatible positions had produced an impasse, the compromise said in effect: we, the government, wage the war in Vietnam for our security, but will permit your protest provided it is only a little disorderly. The demonstrators: we still consider the war outrageous and will therefore break the law, but not by very much.

Faced with the odd occasion of a gesture of revolution that has been negotiated in advance with the power it wishes to overthrow, Mailer nevertheless concludes that the protests did still do some good, as a “rite of passage” for the “spoiled children of a dead de-animalized middle class,” comparable in its way to the journeys of their pioneer and immigrant ancestors. And we know, though Mailer did not at the time, that public opinion really did in certain ways move the needle on Vietnam, contributing to the end of the draft and LBJ’s declining to seek re-election (Though it could also be argued that the Machine simply found ways to adjust, and by the early 1970s the war in Vietnam was more indiscriminately murderous than ever. That’s at least the impression I got reading Nixonland, but I leave it to the historians.). But the whole affair, as it ends, dwindles into a quiet melancholy. Many protestors leave overnight, those who remain are eventually ordered to disperse or be arrested, and by the end of the day the protest passes into history, to be reported on sympathetically by the Village Voice and unsympathetically by the Times, bolstering the extant prejudices of their respective readers and doing little else. Was it worth it? Did they lob a stone in the gears of the great machine, or was it simply a symbolic gesture, one that allowed its participants to let off some steam before returning to their daily lives? The question floats uncomfortably in the air.

Mailer’s own politics, while he is broadly a part of the Left and the anti-war movement, are individualistic, he calls himself a “Left Conservative” who tries to “think in the style of Marx to attain certain values suggested by Edmund Burke.” This intriguing formulation brings me to the aspect of The Armies of the Night I found most valuable, if also rather frustrating—Mailer’s deep distrust of his fellow liberal intellectuals and his critique of a larger trend towards totalitarian technological control on both left and right, symbolized by the hulking occulted edifice of the Pentagon itself, which he elaborates on in passages such as this one from the opening pages of the novel, which finds him at the well-appointed home of a liberal academic:

If the republic was now managing to convert the citizenry to a plastic mass, ready to be attached to any manipulative gung ho, the author was ready to cast much of the blame for such success into the undernourished lap, the overpsychologized loins, of the liberal academic intelligentsia. They were of course politically opposed to the present programs and movements of the republic in Asian foreign policy, but this political difference seemed no more than a quarrel among engineers. Liberal academics had no root of a real war with technology land itself, no, in all likelihood, they were the natural managers of that future air-conditioned vault where the last of human life would still exist.

Here I find myself at a political impasse, and I will allow myself, hesitantly, to make some comments on Current Events. I agree basically entirely with this passage, and indeed, part of the reason I was drawn to whatever constitutes the scene or circle I find myself affiliated with on this website is because they were the only ones in that seemed to be making a similar critique honestly, without (for the most part) using it as a cover for some equally insidious political agenda. In the last six months, of course, the oh-so-Sixties critique of Mass Man, the Technological Society, and so forth has been the furthest thing from anyone’s mind, and the present danger is not the best and the brightest in thrall to spreadsheet madness, pursuing irrational goals in the name of rationality, but the exact opposite, capricious individuals running roughshod over our precious systems, which I now find myself hoping are strong enough to sustain the attack. But I suspect this critique will become necessary again soon enough, perhaps much sooner than we think.

It should be said that Mailer’s celebration of the earthy and the instinctual and rejection of the mechanistic and totalitarian often leads him to places I would not follow: to the vulgar essentialism of essays like “The White Negro,” to an odd pro-sex but anti-contraception stance that lead him to claims like “condoms are one element in a vast, unconscious conspiracy to make everyone part of the social machine,” (this from, of all things, a 1994 interview with Madonna; the queen of pop looked on, bemused) and, most infamously, to the drunken stabbing of his second wife at a party in 1960, an act which hovered over the rest of his career. It is far too convenient in this case to claim that the writing and the man can be easily separated, when the public proclamations and views and acts flow so naturally from the ideology expressed in the work. So I understand why Mailer comes in for such harsh censure (and if you want to understand why such censure felt so necessary at the time, look up how eminences like Baldwin and Trilling reacted to the stabbing incident). His flaws are much more damning than those of Gornick’s fellow targets Bellow and Roth, and if such an fidelity to one’s baser impulses constitutes Left Conservatism, I can’t say I cosign it.

Yet there remains something irresistibly true, necessary, and attractive in his outlook; in his making of the case at length, like a transcendentalist, for his own self and all the contradictions, foolish thoughts, and buzzing energies it contains. Such a stance manages to tack against both the vile and contemptible bigotry of the right and the compulsory soul-engineering and managed decline of the left, to stand athwart the tides of history and politics and claim for oneself not just subjecthood but personhood. The whole time I was reading The Armies of the Night I was reminded of no one so much as Whitman, who also placed himself as an observer in the great social conflict of his time and whose task was also to examine himself with so much rigor that his act of egotism became something cosmic. This remains a dangerous path. I’m still unsure whether or not the barbaric yawp must by its nature always be sounded at the expense of others; the example of Mailer would seem to indicate that perhaps it must and this, too, is troubling. But it is the task of the writer to negotiate that problem in his or her own way, and Mailer’s example provided for me, if not a model to emulate precisely, a set of possibilities overlooked in our more decorous and circumspect times. For that at least I say: thanks, you old putz.

For shaping my underlying thinking about these midcentury Jewish writers I am indebted to conversations with

and also to , who writes with sympathy and intelligence about these various blowhards, and on the political side to for his recent eloquent quasi-manifesto.

Fabulous piece Henry. Very smart, very reflective. Good to see Mailer dealt with without all the cultural floss in the way.

Appreciate the shout out! I haven't gotten into Norman Mailer yet so this piece did a lot to fill in the shaky outline of the man in my head. In high school I read Miami and the Siege of Chicago during an embarrassingly long period of obsession/idolization of hippies and other Boomer drug subcultures, but that's about it. I do think the intellectual culture is poorer for its present lack of epic, self-mythologizing characters like Mailer. Who among us has the courage and stamina to commit to such brash unlikeability in public? Certainly not I.