The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

Nine Stories by J.D. Salinger

Franny and Zooey by J.D. Salinger

Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour, An Introduction by J.D. Salinger

In just a few weeks I’ll be thirty. O dark dark dark! All passion spent! Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun! And so on. The window for being a wunderkind has officially closed, no longer can I coast on my innate freshness and vigor. No more “having potential.” No more blaming my immediate problems on being young and foolish. No more discounts or avuncular fancy-seeing-you-here looks at our institutions of higher culture. And if I don’t get it together quickly, I have only a very short few years before I start seeing a new, quietly troubling look in people’s faces, a look that says: shouldn’t you have accomplished a bit more with your life?

I’m just joking, mostly. Please don’t leave any sage advice in the comments. It is undeniably true, though, that there are certain writers that make more sense when you’re young, a certain receptivity and guilelessness you possess that fades away for most people as they age (it is equally true, of course, that many writers begin to make complete sense only later in life). These writers tend to be evaluated in the critical organs of the Western world like any other major figure, but in these evaluations one detects a certain sheepishness, a certain ladies-and-gentlemen-of-the-jury quality, as if the critic is worried that their peers will come up to them looking concerned and say, in a conspiratorial mutter, “isn’t he a little, you know…juvenile?” Often they will have a coterie of defenders; biographers, fan society members, YouTube lecturers, and so on, who will say not just that they are worthy of serious critical attention but are in fact among the pinnacles of the written word itself, overlooked and dismissed by dust-dry academics who have forgotten what it means to live, goddammit, really live. You probably know who I’m talking about. Herman Hesse. Kurt Vonnegut. Kerouac and Ginsberg. And, reputation contorted in a somewhat uncomfortable position between this world and the world of a more staid and respectable literary establishment, J.D. Salinger.

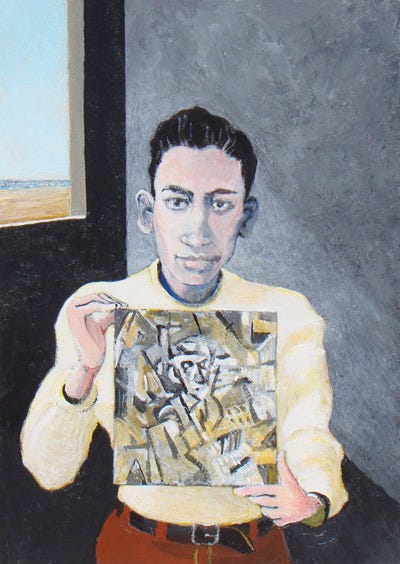

So it was that I, after reading an essay by Craig Raine full of praise for The Catcher in the Rye1, realized that I had never read a single word by Salinger, and it suddenly seemed obliquely important that I fit him in there before that fateful day, in case some sort of mental gate slams shut and I find myself trapped forever in world-weary middle-age. Luckily his published oeuvre is quite small and I could read it all, some uncollected stories aside, in a week and take another few days to write about it. So off I went.

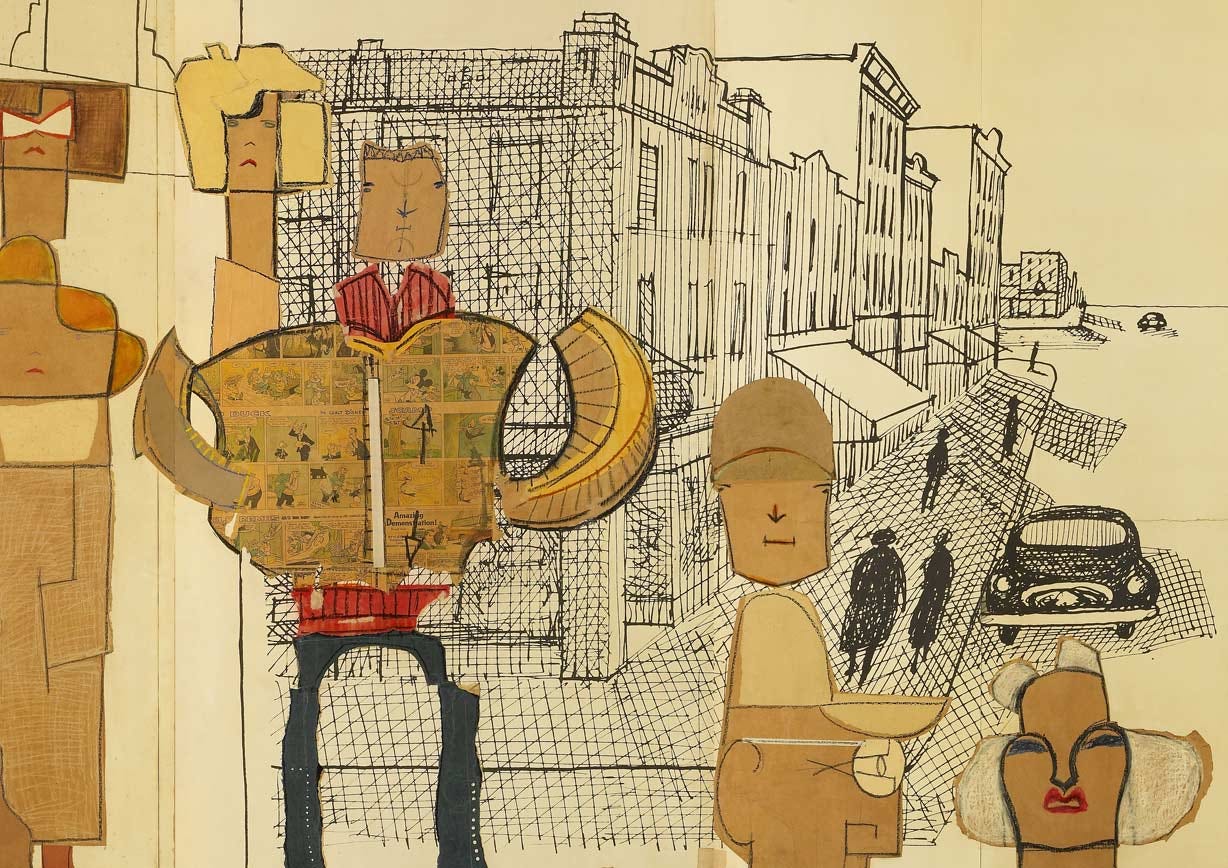

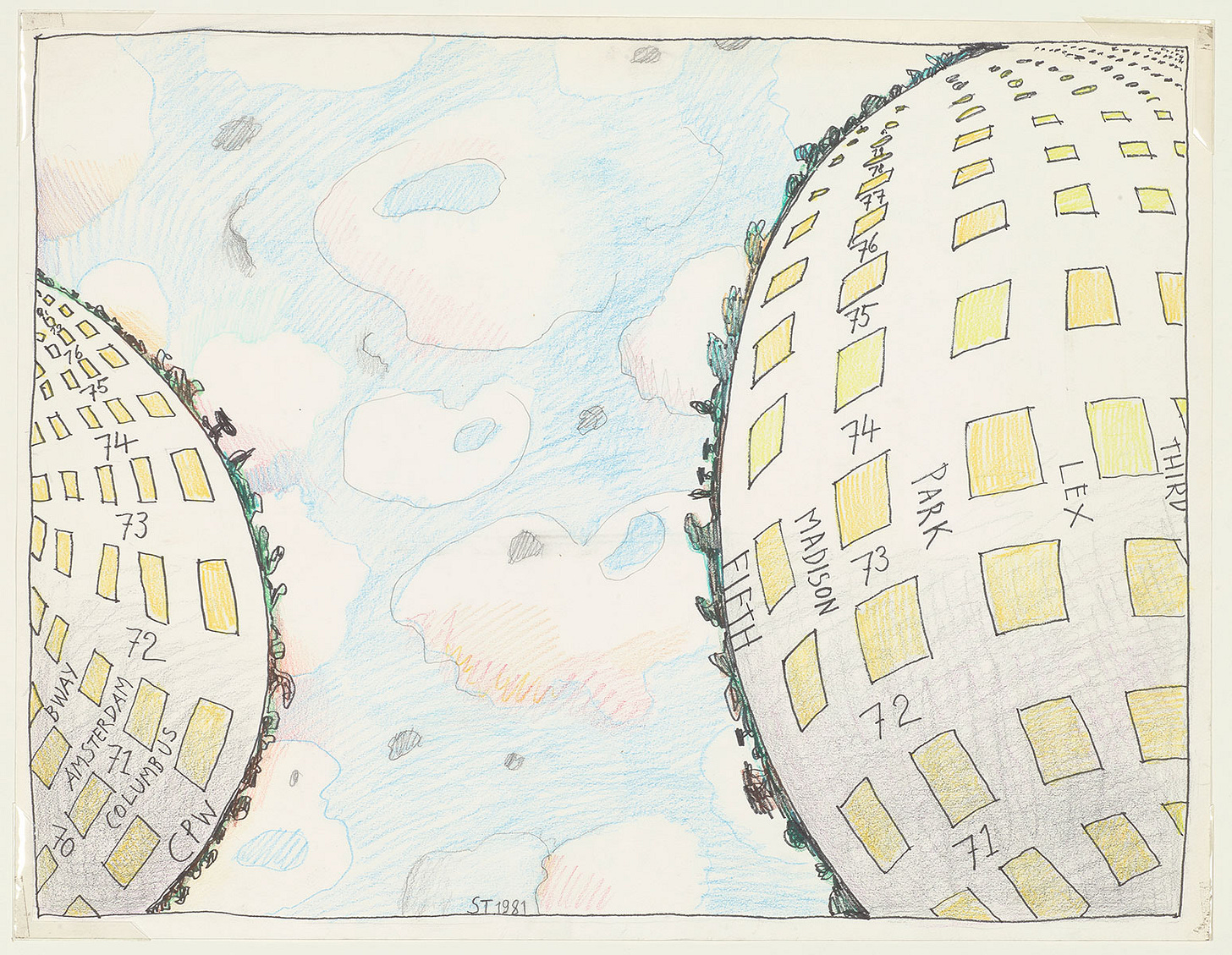

The Catcher in the Rye. You know it, you love it. Actually, it’s more likely that you hate it, to judge by the prevailing sentiments online. Maybe you were forced to read it in school. Maybe—this is what happened to me—innumerable adults in your life tried to press it on you. “You’ll love it,” they all said. “He’s an angsty teen, just like you.” For my readers with young children, you should know that this is an excellent way to ensure a book will never, ever be read. Anyway, you know how it goes. Holden Caulfield, archetypal troubled teen, gets kicked out of prep school and spends a few days drifting around New York City processing the recent death of his younger brother while having a series of memorable encounters with the denizens of the urban jungle, eventually, in the first of many instances of Salinger’s emotionally repressed men finding emotional solace in an encounter with a young girl, coming to some point of catharsis through his relationship with his beloved younger sister Phoebe.

I feel somewhat vindicated in rejecting Catcher at fifteen because I think I would indeed have disliked it, seen it as condescending and corny and dated (I was a Grant Morrison/Alan Moore/William Blake kid at that age anyway). Now older and possibly wiser, I do admire many aspects of it. It’s obviously undeniable that Holden is a very memorable and amusing narrator and the overall atmosphere of wry, wintry, Upper East Side melancholy made many of its successors—Metropolitan, The Royal Tenenbaums, etc—suddenly click into place. And the climax of the book, where Holden rejects the only adult who appears to understand and care for him after a masterfully ambiguous, possibly-but-possibly-not-pederastic interaction and seeks refuge in Phoebe’s innocence, is genuinely moving. Assuming you’re not one of the people who loudly proclaim to anyone who will listen how annoying and privileged you find Holden, your heart breaks for the poor, lonely kid.

But overall it is not quite what I hoped it would be. The vibe is less “beloved classic" and more “NYRB Classic,” in the sense of a B/B+ book dug up from the archives and made interesting in part by its evocation of another world and another time. Craig Raine (aforementioned) places Catcher in the tradition of the “great soliloquy of American vernacular…From Huck to Holden to Herzog the line of language stretches itself—unbroken, supple, sassy, streetwise.” That might be true, technically. But it’s actually pretty difficult, if you try, to write a convincing imitation of Huck, or Portnoy, or Augie March. Holden, on the other hand, is easy to imitate, which is why every goddam phony critic feels the temptation to do it in all their crumby essays. There is something about all that affected teenage slang that acts as a sort of crutch for a narrative voice that one feels should come from the deeper rhythms of the text, not just from a set of rhetorical flourishes2. Reading Catcher, I felt as if I could see Salinger, young, sensitive, and talented himself, deciding to inhabit the role of this young, sensitive, and talented teenager and the methods that he was consciously employing, whereas I rarely feel that sense of authorial presence in the other, wonderfully naturalistic, famous American novels of soliloquy. The overall effect can be just a bit—Christ, do I have to say it? Phony.

Teenage narrators like Holden are an extraordinarily tricky balancing act for any author. In every book written in the first person there is already a sort of double consciousness, where as a reader, you inhabit the consciousness of the book’s narrator while also passing judgement on their actions in your capacity as a free-thinking individual. When the subject of the book is the transition from childhood to adulthood, added to this double consciousness is the knowledge that comes with aging, the emotional realities that are obvious to an adult and invisible to an adolescent. This overloading of narrative irony, this I-know-that-you-know-that-I-know on the part of the author and the reader, can so easily get too heavy and cause books to topple, especially when the author gets a bit obvious with it.

When I was really drunk, I started that stupid business with the bullet in my guts again. I was the only guy at the bar with a bullet in their guts. I kept putting my hand under my jacket, on my stomach and all, to keep the blood from dripping all over the place. I didn't want anybody to know I was even wounded. I was concealing the fact that I was a wounded sonuvabitch.

Passages like that have me thinking of The Great Gatsby, an avowed influence on Salinger, which Holden name-checks towards the beginning of the book. I love Gatsby, but the reason it and Catcher share space on AP Lit curriculum (or did until very recently I suppose, when they still had students read full novels) is because they provide English teachers with something concrete to point to, with all this talk of Gatsby’s green light, Holden’s bullet in the guts, and his fantasy of being the “catcher in the rye” who saves children from falling, as screamingly obvious “symbols” that the student is supposed to correctly decode to prove she “understands” the book. Fitzgerald, for whatever reason, because of his skill in description or the perfectly formed tragic arc of Gatsby, gets away with it. Salinger, for me, not so much.

So after Catcher I got a bit nervous that all of these books were going to be medium-good at best. But I needn’t have worried. Nine Stories is wonderful; it’s hard to imagine how it could be better. “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” “For Esme—With Love and Squalor,” and “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period”—these are just about as good as it gets, the others are very very good indeed, and only “Teddy,” which features a precocious child explaining the basics of Eastern philosophy before meeting an ambiguous fate, shades, in a slightly ominous foreshadowing of Salinger’s later preoccupations, into being a bit annoying. Most of these stories were originally published in The New Yorker, and reading them made me think of how I used to pick up my parents’ copy and come away from the fiction section slightly disgusted. This was what adults wanted to spend their time reading about? Mannered stories about boring upper-middle class people where nothing even happens?

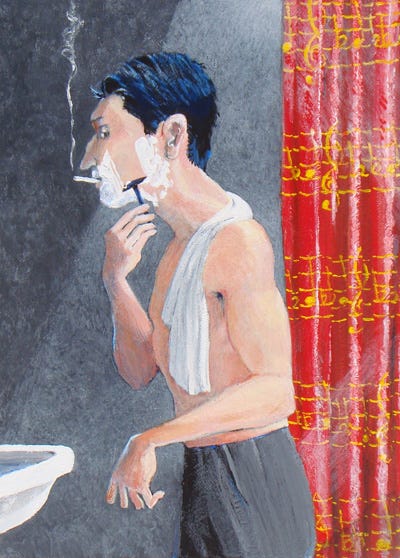

It’s still difficult to explain exactly what it is about these stories that makes them so good. In contrast to Catcher’s over-explanatory nature, they leave much unsaid, letting everything come out naturally through the masterful and realistic dialogue. Like Hemingway, Salinger was traumatized by war, and perhaps this accounts for their shared tactic of dealing with extremes of emotion through understatement and implication. But where Hemingway wrote of taciturn, stoic man’s men, Salinger mostly deals with quotidian, slightly bohemian upper-middle-class life. And of course, a lot of people went through extreme trauma in the war, and very few of them became the great writers of postwar America. Perhaps the appeal is better explained by the following anecdote.

There’s something that happens to me occasionally, maybe once a year if I’m lucky, when I finish a really really good novel. It’s a sort of fleeting Buddhistic awareness or minor spiritual awakening. I still remember the morning I finished Little, Big by John Crowley and walked out of my ugly, drab apartment on an ugly, drab Los Angeles street and suddenly saw the pomegranate tree outside my door in the true fullness of its being. I had walked by it probably hundreds of times and never really seen it. Salinger’s short stories, though they didn’t have this exact effect on me, are attempting to work their way through the same phenomenon. Almost all of them feature this sudden epiphany or shift in consciousness. This has of course become the standard way to write a short story in the last century; outside of genre fiction, there are very few Poes or O. Henrys out there writing stories with a standard plot moving from A to B. When I was younger I had a hard time recognizing epiphany’s validity as a literary device, which partially explains my earlier rejection of the New Yorker style (of course, a lot of them are simply bad)3. But reading these stories, which seem to have been transmitted from some reality just a little more heightened, strange, and mystical, a little bit more aware of the world stripped of the blinkers of everyday consciousness, helped me understand how it is that one of the functions of literature, if not the function, can be as a tool that briefly shocks one into that sort of awareness. At least for people like me, who are too dumb or impatient to read European philosophy or contemplate the classic spiritual texts.

Franny and Zooey and Raise High/Seymour make up Late Salinger, where he dives very deep into his fictional Glass family, a group of sensitive, too-good-for-this-world former showbiz kids all haunted by the suicide of their saintly eldest brother Seymour, depicted at the end of “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.” To his defenders it is one of the most fascinating and fully realized portraits of a family in American fiction, to his detractors it marks the period where his protagonists become even more annoying, self-satisfied and cutesy and his puddle-shallow understanding of mysticism and Eastern religion barges its way into the text. Both collections consist of two stories, opposite sides of a coin. In both cases the first story shows members of the Glass family attempting to make their way among the normies of the world. “Franny” shows the titular character attempting to keep it together while having lunch with her boyfriend, and eventually falling into a spiritual crisis. “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters” is a long comic set piece depicting Buddy Glass attempting to entertain a group of judgmental strangers after Seymour skips out on his own wedding. The second story in each case turns inward, sometimes maddeningly so. “Zooey” consists mostly of two long, stifling dialogues in the Glass family apartment and “Seymour: An Introduction” is the most rambling and shaggy Salinger story yet.

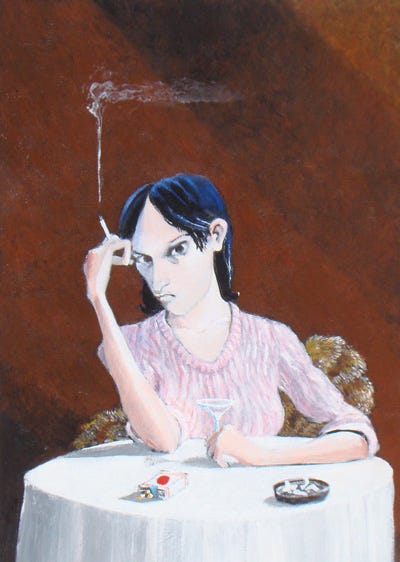

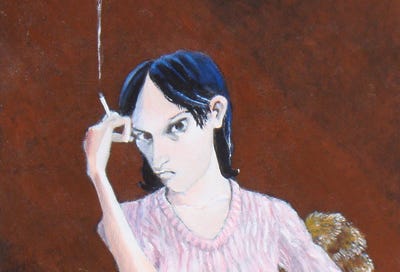

In both cases, the first story is much easier to love, if you’re not on Salinger’s wavelength. “Franny” in particular, the only one of the late four to be short-story length instead of novella-length, is one of his best. Both its social preoccupations—a sensitive girl in thrall to Christian mysticism and her disengaged, faux-intellectual boyfriend—and the structure of its clipped dialogue, in which two lovers circle around one another, both trying to breach the fortress of the other to achieve a form of intimacy or understanding made impossible by social expectations, read as thrillingly contemporary, akin to someone like Matthew Gasda. In dialogue like this, you almost wait for someone to pull out their phone and start scrolling:

"You want another one?" Lane asked Franny.

He didn't get an answer. Franny was staring at the little blotch of sunshine with a special intensity, as if she were considering lying down in it.

"Franny," Lane said patiently, for the waiter's benefit. "Would you like another Martini, or what?"

She looked up. "I'm sorry." She looked at the removed, empty glasses in the waiter's hand. "No. Yes. I don't know."

Lane gave a laugh, looking at the waiter. "Which is it?" he said.

"Yes, please." She looked more alert.

What has happened to Franny, misread by both Lane and many of the story’s early critics as pregnancy, is a sudden, horrible anti-epiphany. Like Holden, and like the narrator of “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period,” she has recognized the essential meaninglessness and falseness of human self-image, how everyone is just an actor playing a role for the benefit of themselves and those around them. It’s up to Zooey (her brother, confusingly, short for “Zachary,” and an actor by trade) to break her out of it, which at the end of the long, claustrophobic story bearing his name, he does, in a now-famous monologue about the “Fat Lady,” the inherent divinity within every person.

I don't care where an actor acts. It can be in summer stock, it can be over a radio, it can be over television, it can be in a goddam Broadway theatre, complete with the most fashionable, most well-fed, most sunburned-looking audience you can imagine. But I'll tell you a terrible secret—Are you listening to me? There isn't anyone out there who isn't Seymour's Fat Lady. That includes your Professor Tupper, buddy. And all his goddam cousins by the dozens. There isn't anyone anywhere that isn't Seymour's Fat Lady. Don't you know that? Don't you know that goddam secret yet? And don't you know—listen to me, now—don't you know who that Fat Lady really is? . . . Ah, buddy. Ah, buddy. It's Christ Himself. Christ Himself, buddy.

The same revelation, more or less, happens at the end of “De Daumier-Smith” as well as “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters.” It’s worth bearing in mind, of course, but heard so many times in quick succession, it starts to have the quality of didacticism, and one begins to ever so slightly resent Salinger, who certainly was no saint in his personal life, for preaching it. And the question remains: if he was so spiritually advanced, why did Seymour, treated as a sort of departed saint or bodhisattva throughout, kill himself in the first place?

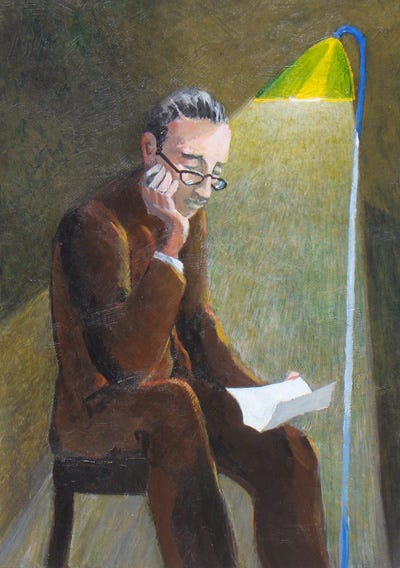

But now I find myself talking about him like a real person, which goes to show the strange power of Salinger’s creations. After the genteel Woody-Allen-ish comedy of “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” “Seymour: An Introduction” comes as something of a shock. It consists of a long monologue by Buddy purportedly discussing his brother, but containing various meta-commentaries on writing and poetry and excursions into family history (foreshadowing Nathan Zuckerman, Buddy names himself as the writer of Catcher and “Bananafish”). It doubles back on itself, contradictory and strange. Salinger’s sentences, previously models of midcentury clarity, become jazzy, quirked-up Henry James:

In this entre-nous spirit, then, old confidant, before we join the others, the grounded everywhere, including, I'm sure, the middle-aged hot-rodders who insist on zooming us to the moon, the Dharma Bums, the makers of cigarette filters for thinking men, the Beat and the Sloppy and the Petulant, the chosen cultists, all the lofty experts who know so well what we should or shouldn't do with our poor little sex organs, all the bearded, proud, unlettered young men and unskilled guitarists and Zenkillers and incorporated aesthetic Teddy boys who look down their thoroughly unenlightened noses at this splendid planet where (please don't shut me up) Kilroy, Christ, and Shakespeare all stopped - before we join these others, I privately say to you, old friend (unto you, really, I'm afraid), please accept from me this unpretentious bouquet of very early-blooming parentheses: ( ( ( ( ) ) ) ).

It’s easy to find this grating and schticky and a lot of people do. And yet something about Salinger/Buddy’s fierce love for the title character, who, perhaps purposefully, is never fully defined to the reader’s satisfaction, makes the novella worth the struggle (though I would recommend reading it only after you’ve finished the rest). It makes it ever more apparent what Salinger was striving at: the question of how to live, how to function in the world, and exactly how aware you ought to be of its transience and illusory nature without going completely nuts. In Seymour, he wanted to create a portrait of someone who had figured it out, but this is obviously an impossible task, so Seymour slips through Salinger’s fingers and through those of every reader. But the beauty is in the trying, which manifests itself through the ever-stranger, ever-more circular work.

Speaking of nuts, it’s finally time to feed a couple of peanuts to the elephant in the room. If anyone knows anything about Salinger at all, it’s that went into reclusion and refused to publish anything for the second half of his life. Towards the end of last century, a spate of memoirs by his children and former romantic partners revealed he was living in the New Hampshire woods, pursuing one spiritual fad after another, from macrobiotic diets to Scientology to Vedanta Hinduism, and taking inappropriately young lovers to whom he was prickly, controlling, and kinda-sorta abusive. I’m not interested in the bad person/good art question, which has been litigated to the point of complete uselessness. But I do wonder if his stories about broken geniuses too sensitive for this sinful earth would be held in the same esteem if he had not essentially become one of these characters.

I think my final judgement has to be yes. The best stories are just about as good as anything else published in the century of the American short story and the longer narratives, maddening, discursive, and interior-bound as they are, are flawed but very difficult to forget. In particular, the way in which he creates an ever-expanding universe of related characters and relationships and seeds information through the opening pages of the Glass books and stories that only becomes clear on a second read makes it clear that he is working in the same complex modernist register as Faulkner, Morrison, and Nabokov (who loved him). Even if his highs are not quite as high as theirs and his philosophy sometimes simplistic or didactic, his work hums with a similar sense of life and complex energy (and if there really is a large cache of unpublished material that will see daylight within the decade, as his son has claimed, then who knows—one day not too far away we might speak of all this as “the early Salinger”). Though I certainly have my reservations about treating him as a saint or a sage, even putting aside whatever he may have been like personally, and I recognize the faults of both the early and the late work, having come to the end of this journey I now understand why he inspires deep love, fierce love. And I think I’ll understand it no matter how old I live to be.

Craig Raine, by the way, who I have been interested in ever since reading Leo Robson’s affectionate tribute to the absolutely bonkers experience of being edited by him, is the best critic I’ve discovered in ages. So good is he that while waiting for my copy of his Haydn and the Valve-Trumpet to ship maddeningly slowly from the UK I read almost all of his later collection In Defense of T.S. Eliot on Internet Archive — you have to be really, really good to get me to read more than ten pages on a computer screen. His essay “Sex in Nineteenth-Century Literature” is now one of my all-time favorite pieces of literary criticism.

Interestingly enough, British critics often adore Catcher while Americans are a bit more circumspect. Besides Raine, Julian Barnes calls it “a virtually perfect book.” Meanwhile Janet Malcolm’s big piece on Salinger has little time for Catcher, preferring to go to bat for Franny and Zooey. Louis Menand, ever the cynic, carefully avoids saying it’s any good, instead musing on whether its popularity is mostly due to teenage nostalgia for childhood or parents wishing to communicate that It Gets Better. Charles McGrath’s 2010 obituary for Salinger harumphs: “The novel’s allure persists to this day, even if some of Holden’s preoccupations now seem a bit dated.” You have to wonder if us Americans, being better steeped in the argot of our country, are a bit less easily impressed by Salinger’s demotic narrative voice.

Harold Ross and William Shawn were doing Barry Bonds numbers back in ‘48, publishing “Bananafish,” “Uncle Wiggly in Connecticut,” and “Just Before the War With The Eskimos” as well as Jean Stafford’s “Children are Bored on Sunday,” Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” and Nabokov’s “Signs and Symbols.” Sheesh!

I used to teach *Franny and Zooey* and still find it very funny and moving. What Salinger does with dialogue and gestures (he found cigarettes useful) is incredibly good. I love Franny telling Lane to "Eat them snails," and also the description of the medicine cabinet in the Glass apartment, and also the fact that there isn't ever going to be an answer to the riddle of Seymour's suicide. I understand that it's one of those stories where you might think everyone would be better off if they just stopped thinking and feeling and watched some TV. We've tried that collectively, though, and it's not that great.

This was great! I remember reading the climax of The Catcher in the Rye at around age 14 and having my first "real literary" experience--just a moment of being emotionally knocked off of my feet and into a state of mind where the world felt strange and new, one of the highs I've been chasing ever since. I haven't re-read the book since then in part because I wondered if, with age, I would no longer appreciate the book and would be unable to re-access that old feeling.

Maybe I should give it a re-read!